Laparoscopic Surgery for an Intussusception Caused by a Lipoma in the Ascending Colon

Article information

Abstract

A colonic intussusception caused by an intraluminal lipoma is a rare disease in adults, in whom it usually has a definite organic cause. In fact, it is either caused by a benign or a malignant condition, both of which occur at similar rates. However, little literature is available on laparoscopic procedures for use in cases of adult colonic intussusceptions. Recently, a 52-year-old woman was admitted to our hospital with abdominal pain of one-month duration. Abdominal computed tomography showed an intussusception with a fat-containing mass in the right hepatic area. Colonoscopy showed a colon lumen occupied by the mass. A right hemicolectomy was performed laparoscopically, and the cause of the intussusception was found to be a lipoma. Before obtaining histological confirmation, we carefully perform a laparoscopic procedure, which required consideration of the relations between the involved colonic segment and other conditions such as the location of main vessels, the anatomical exposure with respect to colonic mobilization and the location of specimen retrieval.

INTRODUCTION

An intussusception is defined as the invagination of the proximal into the distal bowel and is usually encountered in children. In fact, only 5% of the cases occur in adults [1-4]. Of the cases of intussusception in children, 70% to 90% are idiopathic with no structural lead points [2, 3, 5]. On the other hand, a colonic intussusception in adults has an identifiable etiology in about 90% of the cases [6], and of these, a lipoma is the most common cause [7]. In 90% of adult cases, the lipoma arises from the submucosal layer in the colon wall [8]. When this organic lesion is present, the consensus is that surgical resection is the proper treatment [9, 10]. Recently, laparoscopic surgery has been developed, but little is known about laparoscopic surgery for treating a colonic intussusception associated with benign disease. Here, we present the case of a 52-year-old woman with an ascending colonic intussusception caused by a lipoma, and we describe the laparoscopic procedure used.

CASE REPORT

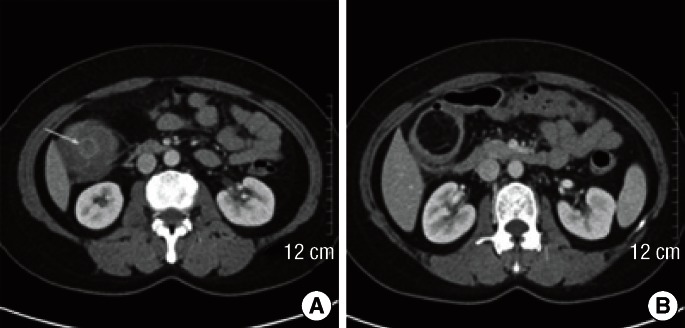

A 52-year-old woman with intermittent right upper-quadrant (RUQ) abdominal pain without hematochezia of one-month duration visited our hospital. She did not complain of other symptoms such as vomiting or nausea, had no relevant medical or surgical history, and denied alcohol consumption and smoking. A physical examination revealed RUQ tenderness, but no rebound tenderness. No abdominal mass was palpated. Laboratory tests showed hemoglobin 12.6 g/dL, hematocrits 37.6%, platelets 339,000/mm3, aspartate aminotransferase 12 IU/L, alanine aminotrasferase 9 IU/L, and total bilirubin 0.43 mg/dL; all other tests were within normal limits. Electrocardiography, chest X-ray, and plain abdominal X-ray findings were nonspecific. The RUQ tenderness caused us to suspect a gall bladder problem. However, abdominal computed tomography (CT) revealed an intact gall bladder and a lesion suspected of being an intussusception with a fatty mass at the hepatic flexure (Fig. 1). In addition, we noted a 4 cm × 5 cm sized intraluminal mass in the ascending colon, which was suspected of being a lipoma (Fig. 2A). The doctor that performed the colonoscopy observed an intraluminal lipoma, and the patient was transferred for surgery.

Computed tomography. (A) The arrow indicates the intussusception with a target-like lesion in the right hepatic area. (B) A 4 cm × 5 cm size fat-containing mass was observed in the intussusception.

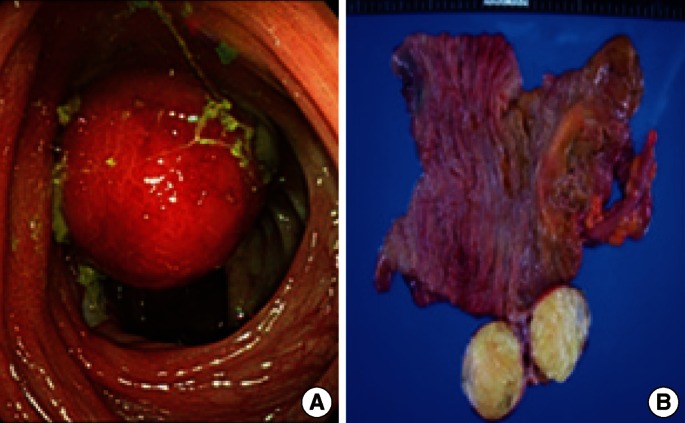

Gross images. (A) Colonoscopic finding. A huge mass was observed in the ascending colon. (B) The resected specimen was a polypoid mass arising from the cecal wall, and its cut surface revealed yellow adipose tissue.

After reviewing the surgical option, we planned for a laparoscopic right hemicolectomy. Under general anesthesia, the patient was placed in the supine position. One port was then placed at the umbilicus (11 mm) for a camera and was used to establish pneumoperitoneum. Additional ports were placed in the left upper and lower quadrant areas for the surgeon. To perform the operative procedure conveniently, we placed two additional ports (right upper and lower quadrant areas) for an assistant. The operating table was then tilted into a slight head-up position with the left side down to easily mobilize the colon at the hepatic flexure. With a harmonic scalpel, the hepatocolic ligament was divided, the ascending colon was then mobilized using an inferior-to-superior approach, and the ileocolic vessels were ligated. Once the entire right colon had been mobilized, it was extracted through the extended camera port site with a wound protector. A right hemicolectomy and side-to-side anastomosis were performed extracorporeally using staplers. The patient recovered without complications, and was discharged 10 days after surgery. The gross finding of the tumor is shown in Fig. 2B; a histological examination proved it to be a lipoma.

DISCUSSION

An adult intussusception is rare and is usually caused by common lead points. About 57% of colonic lesions are benign and 43% to 63% are malignant [1, 11], and a lipoma is the most common benign tumor of the colon that causes colonic intussusceptions in adults [12]. Furthermore, lipomas larger than 4 cm are considered giant and are symptomatic in 75% of patients [7, 13]. Abdominal pain ranges from mild intermittent colicky episodes to severe episodes followed by spontaneous resolution. Recent literature suggests that abdominal CT is the best noninvasive diagnostic modality for a colonic lipoma, which exhibits a homogenous fatty density of between -40 and -120 Hounsfield units [11].

Our doctors did not try to perform an endoscopic procedure, including an endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) and an endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD), within the luminal space because of the size of the lipoma, which filled the luminal diameter, for the following reasons: First, the base of the mass was difficult to identify. Second, the risk of perforation was high because of a relative thinning of the ascending colon wall anatomically. Third, even if the lipoma had been detached from the colon wall, moving toward the anus would have been problematic. Fourth, a point of considerable importance was that the ESD and the EMR were thought to be unsuitable because of the tumor's large size and its ambiguous depth. Therefore, the only treatment option for adult intussusception is surgery. Thus, we planned a segmental resection without manual reduction or endoscopic mass excision due to the risk of malignancy and the possibility for intramural or serosal spreading during manual reduction if this were the case.

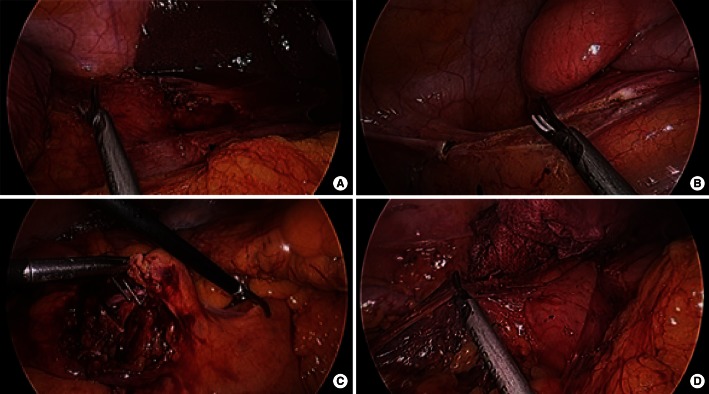

In the case of an adult intussusception, several aspects of the laparoscopic procedure should be considered. First, the range and the location of the intussusception must be ascertained to determine main vessel ligation and the range of the resected mesentery. For example, for long, segmental intussusceptions in the colon, two main vessels, such ileocolic and mid-colic vessels, may be sacrificed. In addition, the involved colonic lesion must be resected fully because an intussuscepted colon wall with edema and inflammation can disrupt anastomoses. Second, there is no priority between a colon mobilization and a vessel ligation in cases of benign tumors. For a malignant tumor, we first perform main vessel and lymphatic channel ligation to prevent the spread of tumor cells, which is an important oncologic rationale. However, if a benign tumor is strongly suspected, this may not be necessary. In the described case, we initially performed colonic mobilization of the hepatic flexure (Fig. 3A) and cecum (Fig. 3B) to provide easy access and to shorten the operation time. Our case showed low ligation of ileocolic vessels because of the low possibility of malignancy (Fig. 3C). However, although the tumor was suspected to be benign, at least the ligation of vessels near the main trunk was the better option because this allowed full colon mobilization, enabled anastomosis to be performed comfortably, and, from the safety aspect, addressed the risk of malignant potential. Third, wound scarring should be considered. Therefore, with the arguments mentioned above, a size of the midline incision, including the umbilicus, can be minimized if we can detach the colonic mesentery both from the retroperitoneum enough to expose the C-loop of the duodenum irrespective of ligation of the right branch of the midcolic vessel and from the right-side omentum partially (Fig. 3D). In brief, the order of the operative procedure and the use of variant approaches depend on the status of anatomical exposure and the tumor's characteristics.

Laparoscopic images. (A) First, the hepatocolic ligament was divided. (B) Second, the ascending colon was mobilized from the base of the appendix up to the hepatic flexure. (C) Third, ileocolic vessels were clipped. (D) Fourth, the right colon was mobilized sufficiently to expose a C-loop of the duodenum for the extracorporeal procedure.

In conclusion, we believe that in cases of intussusception of the ascending colon in adults, laparoscopic procedures are feasible, but resection of the involved colon without reduction should be considered, irrespective of the tumor characteristics.

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.