- Search

| Ann Coloproctol > Volume 37(4); 2021 > Article |

|

Abstract

Purpose

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has strained healthcare resources worldwide. Despite the high number of cases, cancer management should remain one of the priorities of healthcare, as any delay would potentially cause disease progression.

Methods

This was an observational study that included nonmetastatic rectal cancer patients managed at the Philippine General Hospital from March 16 to May 31, 2020, coinciding with the lockdown. The treatment received and their outcomes were investigated.

Results

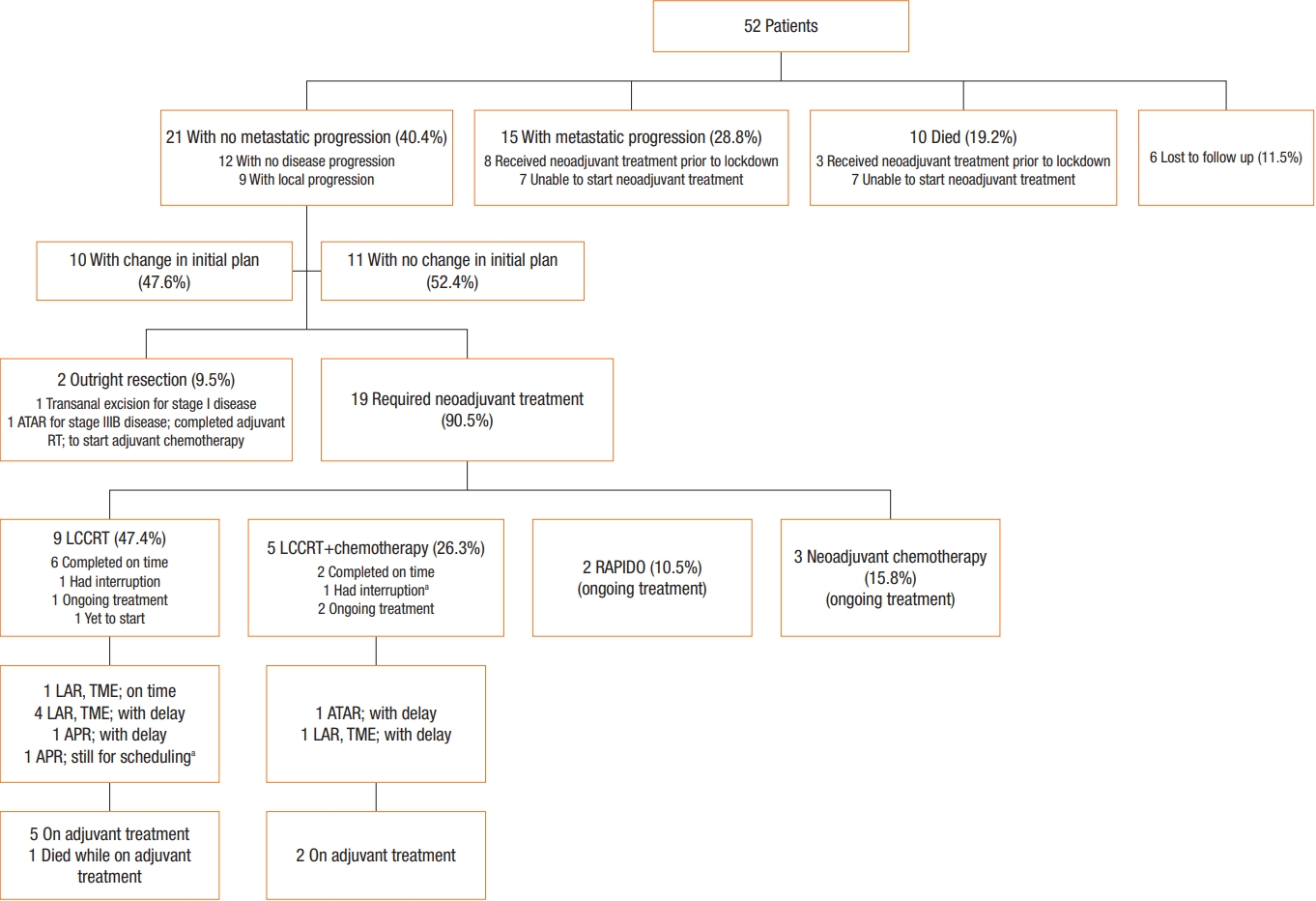

Of the 52 patients included, the majority were female (57.7%), belonging to the age group of 50 to 69 years (53.8%), and residing outside the capital (59.6%). On follow-up, 23.1% had no disease progression, 17.3% had local progression, 28.8% had metastatic progression, 19.2% have died, and 11.5% were lost to follow up. The initial plan for 47.6% patients was changed. Of the 21 patients with nonmetastatic disease, 2 underwent outright resection. The remaining 19 required neoadjuvant therapy. Eight have completed their neoadjuvant treatment, 8 are undergoing treatment, 2 had their treatment interrupted, and 1 has yet to begin treatment. Among the 9 patients who completed neoadjuvant therapy, only 1 was able to undergo resection on time. The rest were delayed, with a median time of 4 months. One has repeatedly failed to arrive for her surgery due to public transport limitations. There was 1 adjuvant chemotherapy-related mortality.

The coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic has significantly strained the healthcare resources of centers worldwide. Action must then be taken to properly allocate and prioritize these resources. In our country, the Philippine General Hospital (PGH), a tertiary government hospital known to offer specialized medical and surgical care, was designated as one of the COVID-19 referral centers. At the same time, the government enforced what it termed as an enhanced community quarantine (ECQ) that restricted the movement of the population. The ECQ was essentially a total lockdown that only allowed travel to those engaged in the provision of services related to basic commodities. Eventually, a modified ECQ (MECQ) was declared, wherein mass gatherings were allowed but in restricted numbers. These circumstances curtailed the services offered by PGH to non-COVID-19 cases, such as those with malignancy.

Despite the high number of COVID-19 cases, cancer management should remain one of the priorities of healthcare, as any delay would potentially cause the progression of the disease. This study looked into the changes in the management of patients with nonmetastatic rectal cancer who have undergone, or were undergoing neoadjuvant therapy; or were scheduled for surgery, prior to the imposition of the ECQ, and how these changes affected outcomes. The short-term outcomes of patients in terms of morbidity, mortality, and compliance upon modification in the treatment plan for rectal cancer were documented.

All patients with nonmetastatic rectal cancer who were actively being managed (have recently undergone, or were undergoing neoadjuvant therapy; or were scheduled for surgery) at the PGH at the time of implementation of the ECQ last March 16, 2020 until the MECQ was lifted on May 31, 2020 were included in the study.

These were patients who already had a treatment consensus after the multidisciplinary team (MDT) discussion as of March 16, 2020, and those who were seen and/or discussed during the conferences until May 31, 2020. Patients with metastatic rectal cancer prior to the implementation of the ECQ were excluded.

Each patient was discussed in the weekly meetings of the University of the Philippines (UP)-PGH Colorectal Cancer and Polyp Study Group, an MDT composed of various stakeholders involved in the care of colorectal cancer patients. To comply with the recommendations set during the pandemic, the team resorted to virtual conferences conducted on an online platform, as these remain essential in the treatment planning of the patients. The list of patients was generated by reviewing the proceedings of the weekly MDT conferences.

The following neoadjuvant treatment strategies were being implemented at the PGH: long-course chemoradiotherapy (LCCRT), short-course radiotherapy (SCRT), LCCRT followed by systemic chemotherapy (LCCRT+chemo), SCRT followed by systemic chemotherapy (RAPIDO [Radiotherapy and Preoperative Induction Therapy Followed by Dedicated Operation] protocol), and neoadjuvant chemotherapy, with the first 2 being the ones more commonly utilized. Surgical management with varying interval from the completion of neoadjuvant treatment then follows, depending on the neoadjuvant treatment received.

LCCRT and SCRT are indicated for rectal cancer patients with T3 to T4 disease, with or without regional lymph node involvement, which corresponds to stage II to III. LCCRT is recommended for patients in need of tumor downsizing especially those with a predicted positive circumferential resection margin (CRM). SCRT is reserved for patients where a negative CRM is predicted in pretreatment imaging. Because recent data show adverse outcomes in conventional SCRT, the potential benefits of RAPIDO are currently being investigated.

Modifications from the previously planned treatment were investigated. Modification in treatment was defined as a change from the original plan of the MDT, for a particular patient, in response to the institutional limitations caused by the pandemic.

Delay in surgical treatment carried varying definitions depending on the neoadjuvant therapy received. For those who received LCCRT, surgery was considered delayed when done beyond 8 weeks after the last day of radiation; beyond a week for those who received SCRT; and beyond 4 weeks for, LCCRT followed by chemotherapy, RAPIDO, and neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

Short-term outcomes of the neoadjuvant therapy set at 90 days from the completion of the neoadjuvant therapy, namely, disease status, compliance to treatment, and toxicity from treatment, were documented. In addition, surgical outcomes in terms of inpatient and 30-day morbidity and mortality were also investigated.

This was an observational single cohort study that included a generation of list of patients with nonmetastatic rectal cancer discussed during weekly MDT conferences. The management received and the resultant short-term outcomes of the neoadjuvant treatment and the surgical intervention were investigated. A data collection form for each patient was filled out. Frequencies and percentages were reported.

This study was delimited to the description of the initial impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in the treatment of patients with nonmetastatic rectal cancer. The data gathered from this observational study can therefore be used for a follow-up study with a larger population. An investigation with a control group comparing the situation before and during the pandemic, with emphasis on the adjustments in the treatment practices of rectal cancer can be done.

This study was conducted while taking into consideration the guidelines set in the Helsinki Declaration, and was reviewed and approved by the University of the Philippines Manila Research Ethics Board (UPM REB) (No. 2020-495-01). A waiver of consent was requested from UPM REB as this study only included collection of nonsensitive data and did not employ any new intervention. Measures were taken to ensure the privacy and anonymity of the patients included in the study. Code numbers were used for each patient, and all data collection forms were solely for the perusal of the authors. No breach in confidentiality happened during the course of the study. The data collection forms were disposed of, and all electronic files were deleted.

A total of 52 patients were included in the study. The majority were female (57.7%), were residing outside the capital (59.6%), belonging to the 50 to 69-year age group (53.8%). Only 1 was reported to have contracted COVID-19 during her course of treatment. The majority of them were stage IIIB at the time of diagnosis. A summary of the patient demographics is shown in Table 1.

Of the patients included in the study, 63.5% underwent bowel diversion either prior to starting treatment, or as a means of palliation after progression to advanced disease. On follow-up, 23.1% had no disease progression, 17.3% had local progression, 28.8% had metastatic progression, 19.2% have died, and 11.5% were lost to follow up.

Among the 21 patients with nonmetastatic disease, 2 were to undergo outright resection, but 1 decided to have her surgery done in her locality. The remaining 19 required neoadjuvant therapyŌĆö9, LCCRT; 5, LCCRTs followed by systemic chemotherapy; 2, SCRT followed by systemic chemotherapy (RAPIDO); and 3, neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

Eight have completed their neoadjuvant treatment, 8 are undergoing treatment, 2 had their treatment interrupted during the lockdown due to the temporary suspension of hospital service for non-COVID-19 patients, and 1 has yet to begin treatment. No treatment-associated complication was reported. The initial plan for 10 patients, as agreed upon by an MDT, was modified (Table 2).

Among the 9 patients who completed neoadjuvant therapy, only 1 was able to undergo resection on time. The rest were delayed, with a median time of 4 months. One had postoperative complications (i.e., ileus and superficial surgical site infection). One has repeatedly failed to arrive for her surgery due to the absence of public transport from her residence. There was 1 adjuvant chemotherapy-related mortality.

Fig. 1 summarizes the modifications to treatment strategy, the actual treatment received, the disease status, compliance, and the short-term outcomes of the patients.

Colorectal cancer is the third most common malignancy worldwide, following breast and lung cancer. In 2018, the World Health Organization recorded an estimate of 1.8 million new cases [1]. The overall 5-year survival rate of rectal cancer is 67%. For localized disease, survival rate is 89%. If it has spread to surrounding tissues or organs and/or the regional lymph nodes, this drops to 70%, and further to 15% if it is already metastatic [2]. In the Philippines, an estimate of 9,000 new cases of colorectal cancer are predicted to occur annually, with a 40% of 5-year relative survival rate [3].

In December 2019, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, there was reprioritization of the allocation of health resources. This, in turn, affected the focus given to non-COVID-19 cases, like malignancy. Several factors have been implicated in the increasing burden of COVID-19 on cancer care. In the limited data available, patients with malignancy are at risk of having worse outcomes from the infection. Diagnosis may also be delayed as screening and diagnostic tests have been suspended, and patients are more averse to hospital visits. Treatment plans have also been modified to reduce exposure of patients with cancer to COVID-19 [4].

With the rising number of cases in the country, the Department of Health requested the PGH, one of the largest multispecialty government hospitals, to be a COVID-19 referral center. In addition, the Philippine government declared an ECQ, or total lockdown, on March 16, 2020, in an attempt to prevent the transmission of the disease. This restricted the movement of the general population, and only activities related to basic commodities were allowed.

Prior to the pandemic, the hospital catered to 600,000 patients annually, the majority of whom belong to the lower socioeconomic classes. Consequently, due to the aforementioned factors, there was a decline in number of non-COVID-19 patients being served by the institution, as in the case of patients with malignancies, who require specialized and multidisciplinary care. In the Division of Colorectal Surgery of the PGH, a total of 106 rectal cancer operations were done in 2019 [5]. However, in 2020, an expected sharp decrease in consults and surgeries was seen. For the year, 38 operations were performed prior to the lockdown, while a total of 24 were done during and after its implementation.

Transient adjustments to cancer care delivery were accommodated, which included temporary discontinuation of screening and diagnostic tests, shifting of consultations to telemedicine, and deferment of some elective surgeries. All these were done in anticipation of a surge of patients infected with COVID-19. These limitations led to modifications in the management employed in the care of patients with rectal cancer, taking into account the need to perform cancer surgery at the appropriate time and the risk of nosocomial COVID-19 transmission.

During this time, the hospital administration established new protocols to ensure that urgent and equally important services for non-COVID-19 cases such as cancer will not be further delayed. A separate operating room suite and wards were set up for non-COVID-19 surgical cases. Patients were prescreened and evaluated through telemedicine. All patients and their watchers had mandatory nasopharyngeal severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction swab tests prior to admission for operation, or for procedures like chemoradiotherapy. Healthcare workers also had these periodical swab tests. The new system was in place, and a limited number of elective operations were resumed after 2 months of planning.

The decision to modify, and the eventual planned treatment of patients with rectal cancer, was based on the consensus of the UPPGH Colorectal Cancer and Polyp Study Group. The group, formed in 2007, is an MDT composed of colorectal surgeons, medical oncologists, and radiation oncologists that convene on a weekly basis to discuss the appropriate management for all colorectal cancer patients seen at our institution [6]. On occasion, any of the following may be requested to participate in the discussions: liver surgeon, thoracic surgeon, pathologist, diagnostic radiologist, psychiatrist, palliative care practitioner, and stoma nurse.

The presence of an MDT is instrumental in establishing sound decision for patients with malignancy. The team convenes on a weekly basis to come up with the best treatment plan for the patient. In addition, the enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocol is being widely practiced at the institution as this has proven overall benefits to patients. A nurse coordinator is likewise involved in the care of these patients as he or she is responsible for ensuring that every patient is able to proceed with every phase of treatment without delay.

Fifty-two rectal cancer patients were included in the study. This is an exhaustive list of all nonmetastatic rectal cancer patients generated from the proceedings and files of the weekly MDT conferences. These were patients who already had a plan of treatment as of March 16, 2020, the start of the ECQ, and those who were seen and/or discussed during the MDT conferences until May 31, 2020, the time the ECQ was lifted.

The demographics of patients accommodated during this time is reflective of the population the hospital caters to as government-run tertiary care facilities are lacking beyond the urban centers. The availability, or the lack of it, of specialized cancer centers in the country, remains a concern. More than half (60%) of these patients have the locally advanced disease (stage IIIB) at the outset. Several factors may explain this. Based on observation, among these are lack of patient awareness and poor health-seeking behavior; underutilization of primary healthcare services; absence of a nationwide screening program for colorectal cancer; and failure by physicians to suspect malignancy.

The bulk of the patients with disease progression, or who have died, can be ascribed to the delay in treatment due to the lockdown imposed during the pandemic. Due to the strict restriction in the movement of the population, public transportation was limited in and out of the capital. In addition, since there was reframing of the priorities in the services being provided, there was a temporary delay in the treatment of patients with malignancy. Neoadjuvant radiotherapy and chemotherapy services were temporarily halted, and the operating rooms were reserved for limb and life-threatening conditions. From an international survey conducted by Santoro et al. [7], several factors were enumerated as the reasons for the delay in the diagnosis and treatment of colorectal cancer patients: (1) postponement of MDT meetings, (2) relocation or quarantine of staff members, (3) full conversion of areas and units in the healthcare institution for COVID 19 care, and (4) lack of personal protective equipment (PPE). At the PGH, human resource limitations due to a need to quarantine and PPE concerns were very much felt on the ground.

The initial plan for 10 patients (19.2%), as agreed upon by the MDT, was changed. The primary goal was to reduce the risk of contracting COVID-19 infection from repeated exposure to highrisk areas, while still maximizing treatment options to address the malignancy. In early studies conducted in China and Italy, it was found that cancer patients are at higher risk of developing severe illness when they contract COVID-19 [8, 9]. A tailored approach in treatment is, therefore, recommended. One still has to consider the patients at risk in terms of age and comorbidities, the patientŌĆÖs clinical presentation, the tumor characteristics, the surgical factors, the quality of life during the deferral period, and the condition of the health care system [10]. Several bodies including the American College of Surgeons, the Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons, the Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland, and the Philippine Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons formulated recommendations for the surgical care of colorectal cancer patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. Surgical interventions to cancer patients who are likely to progress, or who require emergency intervention, are the only ones considered necessary [11-14].

Modifications to treatment have been employed to adapt to the limitations caused by the pandemic. In the study of Akyol et al. [10], the treatment of asymptomatic rectal cancers, either by surgery or by giving neoadjuvant treatment, can be deferred up to 30 days [15-17]. Reassessment is to be done after this period, and if no progression was observed, treatment may be delayed for another 30 days. However, if the hospital is still unable to accommodate the patient after 60 days, a repeat radiological staging should be done. The Colon, Rectal, and Anal Cancers Guidelines Panel of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network recommends that for stage II rectal cancer patients who are expected to have a delay in surgical intervention, surgery can further be delayed for up to 12 to 16 weeks if regression was noted on the 8th week after neoadjuvant therapy [18]. For stage III rectal cancer patients, chemotherapy can be given during the 8-week waiting period. If no regression was noted after 8 weeks, surgery should be considered depending on the situation in the institution. For patients who completed LCCRT, assessment should be done after 8 weeks, and if with noted good response, surgery may be delayed further until 16 weeks [10, 12, 18].

In the current setting, the regimen for LCCRT includes capecitabine 825 mg/m2 twice daily, 5 days per week for 5 weeks with concurrent 45 Gy in 25 to 28 fractions to the pelvis. Continuous infusion of 5-fluorouracil 225 mg/m2 intravenously over 24 hours, 5 days per week may also be used. For SCRT, 5 Gy in 5 fractions to the pelvis is given. More recently, the RAPIDO protocol has been employed. This is done by doing SCRT followed by 12 to 16 weeks of chemotherapy. Apart from the promising oncologic outcome, this has gained a new advantage during the pandemic as this lessens the potential exposure of patients to COVID-19 infection because of shorter hospital stays and less frequent visits.

As mentioned, among the 9 patients who completed neoadjuvant therapy, only 1 was able to undergo resection on time. The rest were delayed, with a median time of 4 months. This parallels the findings of the COVIDSurg Collaborative that noted cancellation or postponement of more than 28 million elective operations worldwide during the 12 weeks of peak disruption, 38% of which were for cancer [19]. In a study by Hanna et al. [20], a 4-week delay in surgery translated to 6% to 8% increase in the risk of death. Only 1 had postoperative complications (i.e., ileus and superficial surgical site infection). No pulmonary complications, perioperative COVID-19, nor perioperative mortality were documented. Of note as well is that more than half of the patients included in the study had needed stoma creation. This implies that the cases seen were either already presenting with obstruction either clinically, endoscopically, or radiographically; or that the disease had already progressed. Others with metastatic disease have resorted to bowel diversion as a means of palliation.

In this study, only 1 was documented to have contracted COVID-19 infection while undergoing neoadjuvant therapy. She was asymptomatic. In the multicenter cohort study conducted by COVIDSurg Collaborative, around 50% of patients with perioperative COVID-19 eventually developed pulmonary complications. This translated to a higher 30-day mortality rate. Both these findings were significantly higher when compared to the pre-pandemic baseline [21].

There was 1 adjuvant chemotherapy-related mortality. There was lacking information about the exact cause of death, but the patient experienced severe weakness after the second cycle of chemotherapy, as relayed by her relatives during a telemedicine follow-up.

Surveillance and follow-up had posed another challenge among these patients. Due to the limited number of patients allowed to follow up face-to-face during the peak of the pandemic and the state-mandated lockdown, remote consultation via telemedicine was implemented using a hospital-wide platform. Face-to-face consultations were restricted to patients requiring a more thorough physical examination, or in need of imaging tests.

In conclusion, delays in the management of rectal cancer due to the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in disease progression in several patients. Alternative neoadjuvant treatment options based on sound evidence should be considered while taking into account good oncologic outcomes, acceptable toxicity, and limitation of potential COVID-19 exposure and infection. Investigating the long-term effects of these management principles in a larger population may provide data that support the applicability of these regimens, and establish rectal cancer guidelines during a pandemic, or similar crises.

Fig.┬Ā1.

Summary of rectal cancer patients managed at the Philippine General Hospital (PGH) during the implementation of the enhanced community quarantine in the capital from March 16 to May 31, 2020, as a response to the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic (PGH, 2020). RT, radiotherapy; LCCRT, long-course chemoradiotherapy; RAPIDO, short-course radiotherapy with neoadjuvant chemotherapy; LAR, low anterior resection; TME, total mesorectal excision; APR, abdominoperineal resection; ATAR, abdominotransanal resection.

aDue to unavailability of transportation from their area.

Table┬Ā1.

Demographic characteristics of patients (Philippine General Hospital, 2020)a

Table┬Ā2.

Treatment modifications after MDT discussion of patients with rectal cancer managed during the COVID-19 lockdown (Philippine General Hospital, 2020)

REFERENCES

1. World Health Organization (WHO). Cancer facts sheet [Internet]. Geneva, WHO; 2018 [cited 2021 May 29]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cancer

2. American Cancer Society (ACS). Cancer Facts & Figures 2020 [Internet]. Atlanta (GA), ACS; c2021 [cited 2021 May 29]. Available from: https://www.cancer.org/research/cancer-facts-statistics/all-cancer-facts-figures/cancer-facts-figures-2020.html

3. Laudico AV, Mirasol-Lumague MR, Medina V, Mapua CA, Valenzuela FG, Pukkala E. 2015 Philippine cancer facts and estimates [Internet]. Philippine Cancer Society, Manila; 2015 [cited 2021 May 29]. Available from: http://www.philcancer.org.ph/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/2015-PCS-Ca-Facts-Estimates_CAN090516.pdf

4. Richards M, Anderson M, Carter P, Ebert BL, Mossialos E. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on cancer care. Nat Cancer 2020;20:1ŌĆō3.

5. University of the Philippines Manila (UPM). 2019 Annual reports of Division of Colon and Rectal Surgery, Department of Surgery, Philippine General Hospital. Manila: UPM; 2019.

6. Roxas MF, Lopez MP, Catiwala-an MT, Monroy HJ, Roxas AB, Crisostomo AC, et al. The rectal cancer program at the UP-PGH: institutionalizing the multidisciplinary team paradigm. Philipp J Surg Spec 2009;64:55ŌĆō63.

7. Santoro GA, Grossi U, Murad-Regadas S, Nunoo-Mensah JW, Mellgren A, Di Tanna GL, et al. Delayed COloRectal cancer care during COVID-19 Pandemic (DECOR-19): global perspective from an international survey. Surgery 2021;169:796ŌĆō807.

8. Liang W, Guan W, Chen R, Wang W, Li J, Xu K, et al. Cancer patients in SARS-CoV-2 infection: a nationwide analysis in China. Lancet Oncol 2020;21:335ŌĆō7.

9. Lambertini M, Toss A, Passaro A, Criscitiello C, Cremolini C, Cardone C, et al. Cancer care during the spread of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Italy: young oncologistsŌĆÖ perspective. ESMO Open 2020;5:e000759.

10. Akyol C, Koc MA, Utkan G, Yildiz F, Kuzu MA. The COVID-19 pandemic and colorectal cancer: 5W1H - what should we do to whom, when, why, where and how? Turk J Colorectal Dis 2020;30:67ŌĆō75.

11. The Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland (ACPGBI). Resumption of elective colorectal surgery during COVID-19 [Internet]. London, ACPGBI; 2020 [cited 2021 May 29]. Available from: https://www.acpgbi.org.uk/content/uploads/2020/05/Updated-ACPGBI-considerations-on-resumption-of-Elective-Colorectal-Surgery-during-COVID-19-v17-5-20.pdf

12. American College of Surgeons (ACS). COVID-19 Guidelines for Triage of Colorectal Cancer Patients [Internet]. Chicago, ACS; 2020 [cited 2021 May 29]. Available from: https://www.facs.org/covid-19/clinical-guidance/elective-case/colorectal-cancer

13. Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons (SAGES). SAGES and EAES recommendations regarding surgical response to COVID-19 crisis [Internet]. Los Angeles (GA), SAGES; 2020 [cited 2021 May 29]. Available from: https://www.sages.org/recommendations-surgical-response-covid-19

14. Philippine Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons (PSCRS). PSCRS guidelines for colorectal surgeries during COVID-19 [Internet]. Quezon City, PSCRS; 2020 [cited 2021 May 29]. Available from: https://pcs.org.ph/assets/journals/PCS-PJSS-v75-no1-18-min.pdf

15. Yun YH, Kim YA, Min YH, Park S, Won YJ, Kim DY, et al. The influence of hospital volume and surgical treatment delay on longterm survival after cancer surgery. Ann Oncol 2012;23:2731ŌĆō7.

16. Lee YH, Kung PT, Wang YH, Kuo WY, Kao SL, Tsai WC. Effect of length of time from diagnosis to treatment on colorectal cancer survival: a population-based study. PLoS One 2019;14:e0210465.

17. Strous MTA, Janssen-Heijnen MLG, Vogelaar FJ. Impact of therapeutic delay in colorectal cancer on overall survival and cancer recurrence: is there a safe timeframe for prehabilitation? Eur J Surg Oncol 2019;45:2295ŌĆō301.

18. National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN). Clinical practice guidelines in Rectal Cancer [Internet]. Plymouth Meeting, NCCN; 2020 [cited 2021 May 29]. Available from: https://www.nccn.org/covid-19/

19. COVIDSurg Collaborative. Elective surgery cancellations due to the COVID-19 pandemic: global predictive modelling to inform surgical recovery plans. Br J Surg 2020;107:1440ŌĆō9.