Improved outcomes with implementation of an Enhanced Recovery After Surgery pathway for patients undergoing elective colorectal surgery in the Philippines

Article information

Abstract

Purpose

This study aims to evaluate surgical outcomes (i.e. length of stay [LOS], 30-day morbidity, mortality, reoperation, and readmission rates) with the use of the Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) pathway, and determine its association with the rate of compliance to the different ERAS components.

Methods

This was a prospective cohort of patients, who underwent the following elective procedures: stoma reversal (SR), colon resection (CR), and rectal resection (RR). The primary endpoint was to determine the association of compliance to an ERAS pathway and surgical outcomes. These were then retrospectively compared to outcomes prior to the implementation of ERAS.

Results

A total of 267 patients were included in the study. The overall compliance to the ERAS component was 92.0% (SR, 91.8%; CR, 93.1%; RR, 90.7%). There was an associated decrease in morbidity rates across all types of surgery, as compliance to ERAS increased. The average total LOS decreased in all groups but was only found to have statistical significance in SR (12.1±6.7 days vs. 10.0±5.4 days, P=0.002) and RR (19.9±11.4 days vs. 16.9±10.5 days, P=0.04) groups. Decreased postoperative LOS was noted in all groups. Morbidity rates were significantly higher after ERAS implementation, but reoperation and mortality rates were found to be similar.

Conclusion

Increased compliance to ERAS protocol is associated with a decrease in morbidity across all surgery types. The implementation of an ERAS protocol significantly decreased mean hospital LOS, without any increase in major surgical complications. Having your own hospital ERAS pathway improves documentation and accuracy of reporting surgical complications.

INTRODUCTION

The concept of “fast-track surgery” or “Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS)” was pioneered in the 1990s by Professor Henrik Kehlet, an anesthesiologist from Denmark. It is a bundle of “best evidence-based practices” delivered by a multi-professional health care team, with the intention of assisting patients to recuperate expeditiously after surgery [1, 2]. Clinical (or critical) pathways have been described to improve outcomes in various fields of surgery [3-16], including colorectal surgery [17-23]. Clinical pathways designed for the colorectal surgery patient have resulted in decreased hospital length of stay (LOS) and cost; and decreased, or no difference, in morbidity rates when compared to conventional care [17-21, 23-26].

From the year 2010 to 2014, the Division of Colorectal Surgery at the Philippine General Hospital performed an average of 147 stoma closures, 118 colonic surgeries, and 72 rectal surgeries annually. For patients undergoing stoma reversal (SR), the mean hospital LOS was 17.9 days, while the mean postoperative LOS was 9.1 days. The leak rate was 5.47% [27]. With an average of 1,436 admissions per year to be accommodated to an allotted 14 hospital beds [28], prolonged patient hospital stay greatly impacts on the unit’s capacity to cater to a greater number of patients and contributes to delays in admission and eventual management.

The objective of this study was to determine the association of compliance to the ERAS pathway and surgical outcomes and to compare them with outcomes before ERAS implementation for patients undergoing stoma closure and elective colorectal resections within a resource-limited environment.

METHODS

Study design

This was a prospective cohort study of adult surgical patients admitted by the Division of Colorectal Surgery who underwent any of the following procedures on an elective basis: SR, colon resection (CR), and rectal resection (RR). All patients aged 18 years and above are included in the study. Patients who underwent emergency surgery, had metastatic disease, underwent multivisceral resection, and those undergoing palliative and incomplete tumor resection were excluded from the study. An approval for this study was obtained from the Institutional Ethics and Review Board Committee of Philippine General Hospital (No. (SUR) 2017-087-01) with a waiver for informed consent.

The ERAS pathway

A detailed ERAS pathway was constructed specifically for SR, CR, and RR. All patients were referred to a multidisciplinary team that involved surgeons, anesthesiologists, nurses, nutritionists, and rehabilitation medicine practitioners. Each health care provider accomplished a checklist for the different ERAS components as recommended by the ERAS Society [29, 30]. However, the investigators agreed on some modifications to fit the setting and limitations of our institution. The components of the ERAS pathway with the investigators’ modifications are summarized in Supplementary Fig. 1.

Data collection

Nonsurgical staff research personnel were specifically trained to fill out and complete the data collection form. The data were recorded on an Excel spreadsheet containing information on compliance to ERAS elements, perioperative, and follow-up data. All patients enrolled in the study were followed up until 30 days after discharge to check for development of complications, readmission, reoperation, or unexpected demise.

Outcome

The primary endpoint was to determine the association of compliance to the ERAS pathway and surgical outcomes that included LOS, morbidity, mortality, readmission, and reoperation rates. Secondary endpoint was to retrospectively compare the same outcomes from patients before (pre-ERAS group) and after (ERAS group) the implementation of the ERAS pathway.

Data analysis

A minimum sample size requirement of 89 patients for each procedure was needed to achieve an 80% power and a level of significance of 10% for a 2-sided test of hypothesis using simple logistic regression analysis. This computation was based on a 50% expected probability of having a disease postoperatively among patients who were noncompliant to ERAS and a corresponding odds ratio (OR) of 0.33 (describing the odds of having a disease postoperation among ERAS compliant patients). The computation was performed using PASS 2008 (NCSS, LLC, Kaysville, Utah, USA). Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients. Frequency and proportion were used for categorical variables, and mean and standard deviation for normally distributed continuous variables. The ORs and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) from binary logistic regression were computed to determine if ERAS percent compliance was associated with multiple outcomes such as prolonged LOS, prolonged preoperative stay, prolonged postoperative stay, and morbidity. Null hypotheses were rejected at 0.05 α-level of significance. Stata ver. 13.1 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX, USA) was used for data analysis. The Student t-test, Fisher exact, and 2× 2 chi-square test were used, as appropriate, to determine statistical difference between the pre-ERAS and the ERAS groups.

RESULTS

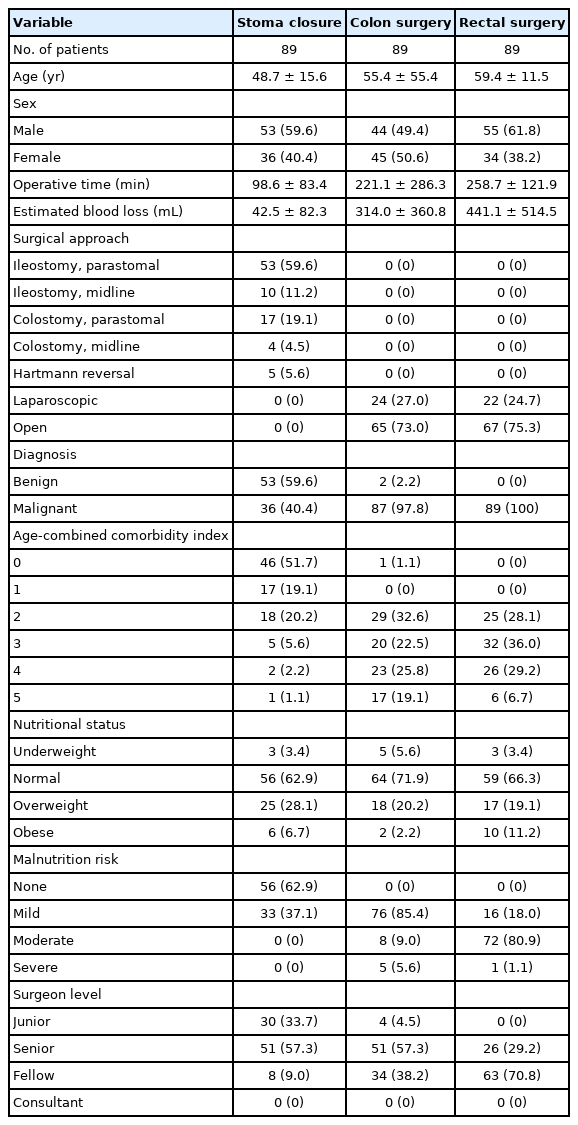

A total of 267 patients were enrolled in the ERAS pathway. Eighty-nine patients were enrolled for each surgical type—SR, CR, and RR. The mean age for SR, CR, and RR were 48, 55, and 59 years, respectively. The patients who underwent CR and RR were mostly cancer patients (CR, 86 of 89; RR, 89 of 89). An open procedure was done on all SR patients, 73.0% for CR, and 75.3% for RR. For SR, majority were ileostomy closure (70.8%). Majority of SR patients had no malnutrition risk (62.9%), CR patients mostly had a mild malnutrition risk (85.4%), and RR patients mostly had a moderate risk (80.9%). Majority of SR and CR (57.3%, respectively) were performed by senior residents; they are the residents of Department of General Surgery who are in the 4th and 5th year of their training. The rest of SR were performed by junior residents (33.7%); they are the residents of Department of General Surgery in their 3rd year of training. For CR, 38.2% were performed by Fellows; they are colorectal specialists in training. These cases were mostly laparoscopic cases. For RR, majority (70.8%) was performed by colorectal specialists-in-training. The consultants are colorectal specialists and they are mostly in supervisory roles during the procedures. The rest of the demographics and clinical profiles of the patients included in the study are shown in Table 1.

Demographic and clinical profile of patient under the ERAS pathway (University of the Philippines-Philippine General Hospital in 2015–2018)

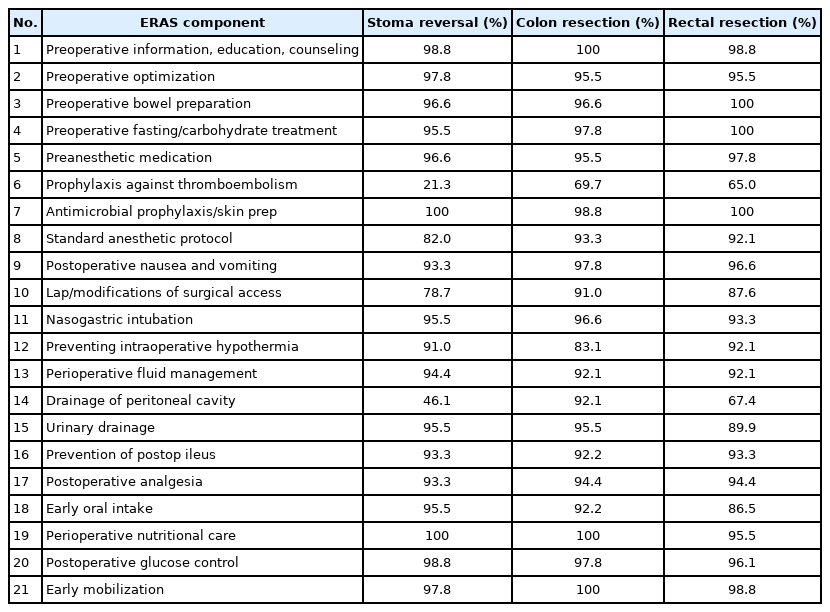

The average compliance of all patients to the ERAS pathway was 92.1% (SR, 91.8%; CR, 93.1%; and RR, 90.7%) and is summarized in Table 2. Logistic regression analysis (Table 3) showed that there was an associated decrease in morbidity rates in SR, CR, and RR, as compliance to the different ERAS elements increased with an OR of 0.96 (95% CI, 0.92–0.99; P=0.012). The compliance for each ERAS category is shown in Table 4.

Compliance rate of patients under the ERAS pathway (University of the Philippines-Philippine General Hospital in 2015–2018)

Compliance rate for each ERAS component (University of the Philippines-Philippine General Hospital in 2015–2018)

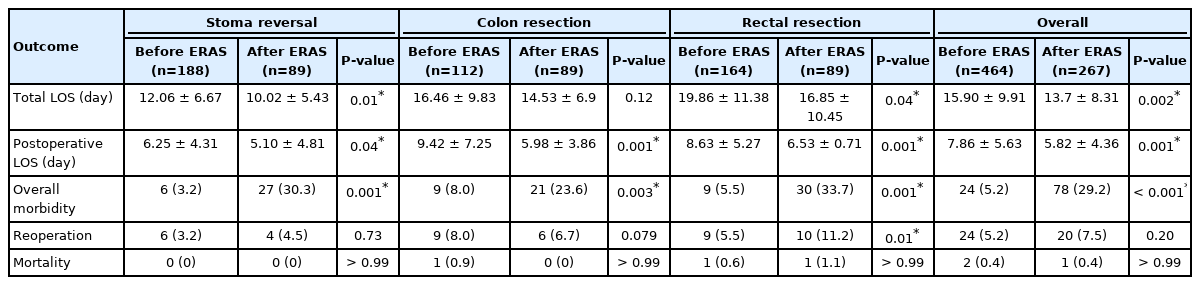

The outcomes obtained after ERAS implementation was compared retrospectively to the outcomes before ERAS. This includes hospital LOS, overall morbidity rate, reoperation rate, mortality rate, and readmission rates. Comparing the 2 time periods, there was a significant reduction in the overall total LOS (15.9±9.9 days vs. 13.7±8.3 days, P=0.002) and postoperative LOS (7.9±5.6 days vs. 5.8±4.4 days, P<0.001) after ERAS implementation. The overall morbidity rate was noted to be increased (5.2% vs. 29.2%, P<0.001), however, the reoperation rate (5.2% vs. 7.5%, P=0.20) and mortality rate (0.4% vs. 0.4%, P>0.99) had no significant difference. These findings are summarized in Table 5.

DISCUSSION

Clinical pathways provide detailed guidance in every step in the management of patients with a specific condition over a given time period, and include progress and outcome details. These aim to improve the continuity and coordination of care across varying disciplines and sectors within the hospital setting. Focus is given to quality and coordination of care among members of a multidisciplinary team [31].

The ERAS protocol was developed in Europe in 2001 and formed the ERAS Study Group. Their goal was to improve not the speed, but the quality of recovery. This concept used a multidisciplinary approach, using scientific and evidence-based protocols, followed by a change in management with an interactive and continuous audit [32]. The combination of these various methods was assumed to lead to earlier postoperative recovery, avoidance of medium-term sequelae of conventional postoperative care, and reduction of hospital stay leading to a decrease in the cost of hospitalization [18]. Applying these principles to clinical practice, meta-analyses by Varadhan et al. [24] and Zhuang et al. [26] have demonstrated that the use of an ERAS protocol versus conventional perioperative care among colorectal patients has reduced hospital LOS, without resulting in differences in complication, readmission, and mortality rates.

The utility of clinical pathways results in standardization of patient care, reduction of hospital LOS, more judicious allocation of resources, and decreased costs without compromising outcome. Compared to conventional practice, which is largely a conundrum of handed-down practices supported by experiential substantiation, the processes involved in a clinical pathway present a more logical, holistic, and evidence-based practice. Evidence of an effective and beneficial clinical pathway process may allow for not only improved patient outcomes, but improved delivery of limited health services as well—a concern that is very much felt in our setting. The Division of Colorectal Surgery handles 1,436 admissions per year with a limited capacity of 14 elective beds [28]. The decreased LOS that can be gained by following the ERAS pathway provides a safe and faster turn-over rate to help our unit cater to more patients and increase our efficiency, particularly in cancer care.

A source of apprehension in implementing ERAS and facilitating earlier patient discharge, particularly for patients who have complications that may have only appeared after they have been sent home, is the potential for readmission. Delaney et al. [33] demonstrated that patients with high levels of comorbidity who underwent complex colorectal surgery have benefited from an ERAS program, with rapid recovery and early discharge with low complication and readmission rates.

In our study, the majority of the patients enrolled under the ERAS protocol were with significant comorbidities and underwent major abdominal and pelvic resections. All patients enrolled in our study were well-informed by a nurse navigator of symptoms that should alert them to seek immediate medical consult, prior to their discharge. Medical care is made accessible to the patient and the caregiver such that in the event that a complication or morbidity is suspected, they can easily contact the nurse navigator and an immediate consult is scheduled for prompt patient assessment by the surgical team. Our results showed a complication rate of 29.2%, a readmission rate of 10.9%, and a reoperation rate of 7.5% (Table 5).

Better outcomes were also observed with better compliance to the ERAS protocol [34, 35]. Our study showed that there was an associated decrease in morbidity rates across all types of surgery as compliance to the different ERAS elements increased (Table 3). Patients that were ≥ 90% adherent to ERAS were less likely to have morbidity. Looking at the compliance of each individual ERAS component (Table 4), the authors believe that had the most important components that have the most impact on outcomes were compliance to standard anesthetic protocol, drainage of peritoneal cavity, and preoperative fluid management.

The implementation of an ERAS protocol has been repeatedly cited in the literature to reduce hospital stay [36-39]. In this study, the mean hospital LOS after ERAS implementation (total LOS, 13.7±8.3 days) was higher compared to the ones reported in the literature by Miller et al. [40] (4.6±3.6 days) and Thiele et al. [41] (6±4.2 days). A primary reason is the patient’s need for admission for supervised implementation of a nutritional plan as many of our patients are in a state of malnutrition on initial presentation. Also, our patients cannot afford nutritional supplements at home, but they can get them for free if they are admitted. This is especially true for patients undergoing CRs. The longer hospital stay may be further explained by certain inefficiencies inherent to our system. Our hospital does not offer a same-day admission and operation. The patients are required to be admitted one to 2 days prior to surgery before they can be scheduled in the operating room. There is also the problem of limited slots in the operating room schedule. There are situations where a patient’s scheduled surgery may be deferred if the early morning cases were extended beyond the allotted time.

On the other hand, the postoperative LOS seems to be improved. The patients after ERAS implementation had a mean postoperative LOS of 5.8±4.4 days. This is slightly higher compared to 4.1 days reported by Sarin et al. [42], and almost similar to 5.66±4.8 days reported by Wahl et al. [43].

Comparing hospital LOS between the 2 time periods (before ERAS vs. after ERAS implementation), it was noted that the overall hospital stay was significantly reduced after ERAS implementation (15.9±9.9 days vs. 13.7±8.3 days, P=0.002). The postoperative LOS was also significantly reduced (7.9±5.6 days vs. 5.8±4.4 days, P<0.001) and was also observed across all types of surgery (SR: 6.25 days vs. 5.10 days, P=0.04; CR: 9.42 days vs. 5.98 days, P<0.001; RR: 8.63 days vs. 6.53 days, P=0.001). This finding is proof that, at least in our institution, ERAS implementation had a significant impact in terms of hospital LOS. A shorter hospital LOS, theoretically, translates to a faster turnaround time for managing patients by the hospital’s colorectal unit.

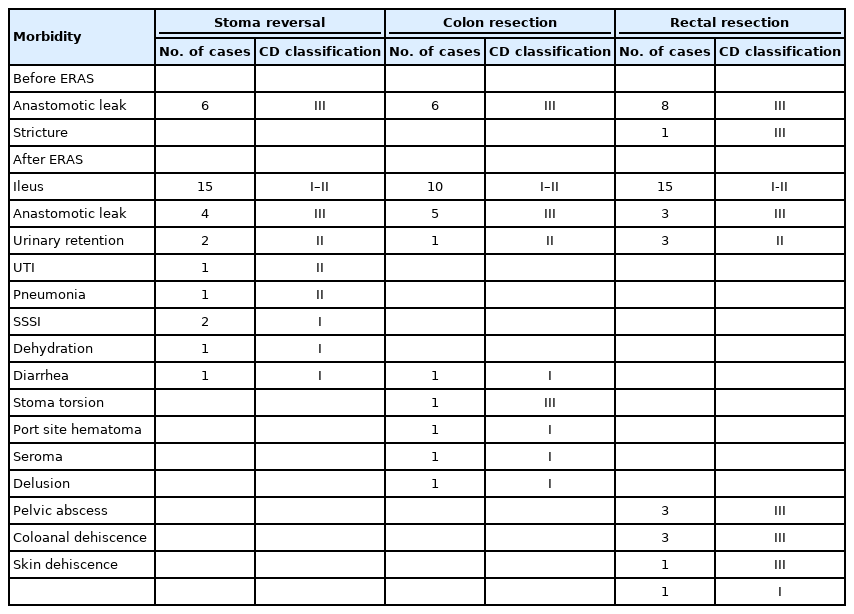

It was also widely demonstrated in the literature that implementation of ERAS decreased complications after colorectal surgery [24]. This was also confirmed with a meta-analysis as reported by Greco et al. [44]. In our study, overall complications increased after ERAS implementation as compared to our data before ERAS. This is because the ERAS pathway provided a platform for caregivers to be more vigilant in detecting surgical morbidities. As part of the protocol, patients enrolled in the ERAS pathway have a checklist that was filled out by the different members of the ERAS team before, during, and after operation. Moreover, an ERAS nurse navigator is in constant communication with the patients even after the patients are discharged from the hospital. Strict adherence to this protocol led to an increased reporting of complications. In comparison with the records before ERAS, it was noted that during ERAS implementation, the documentation of surgical morbidities dramatically improved. Table 6 shows a summary of how morbidities were reported before and after ERAS.

Details of morbidities before and after ERAS pathway implementation (University of the Philippines-Philippine General Hospital in 2015–2018)

Even with increased morbidity noted after ERAS, comparison of the reoperation rate before and after ERAS was noted to be similar (5.2% vs. 7.5%, P=0.20). The mortality rate was also similar (0.4% vs. 0.4%, P>0.99) (Table 5). In addition, before the ERAS was implemented, the data on patient readmission was not reported. With the ERAS pathway in place, we were able to document our readmission rates at 10.86%, which was only slightly higher (vs. 9.2%) than that reported in the literature [45].

In conclusion, increased compliance to ERAS protocol is associated with a decrease in morbidity across all surgery types. The implementation of an ERAS protocol significantly decreased mean hospital LOS, without any increase in major surgical complications. Having your own hospital ERAS pathway improves documentation and accuracy of reporting surgical complications.

Notes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

FUNDING

None.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary materials for this study are presented online (available at https://doi.org/10.3393/ac.2020.09.02).

Supplementary Fig. 1.

Philippine General Hospital-Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (PGH-ERAS) modifications used in the study