- Search

Abstract

Purpose

Malnutrition is associated with an increased risk of developing complications following gastrointestinal surgery, especially following radical surgeries such as pelvic exenteration. This study aims to determine if preoperative body mass index (BMI) is associated with 30-day morbidity, length of hospital stay and/or quality of life (QoL) in patients undergoing pelvic exenteration surgery for recurrent and locally-advanced rectal cancer prior to a prospective trial.

Methods

A review of all patients who underwent pelvic exenteration surgery prior to 2008 was performed. Patients were included if they had a documented BMI as well as a QoL measurement (Functional Assessment Cancer Therapy - Colorectal questionnaire).

Results

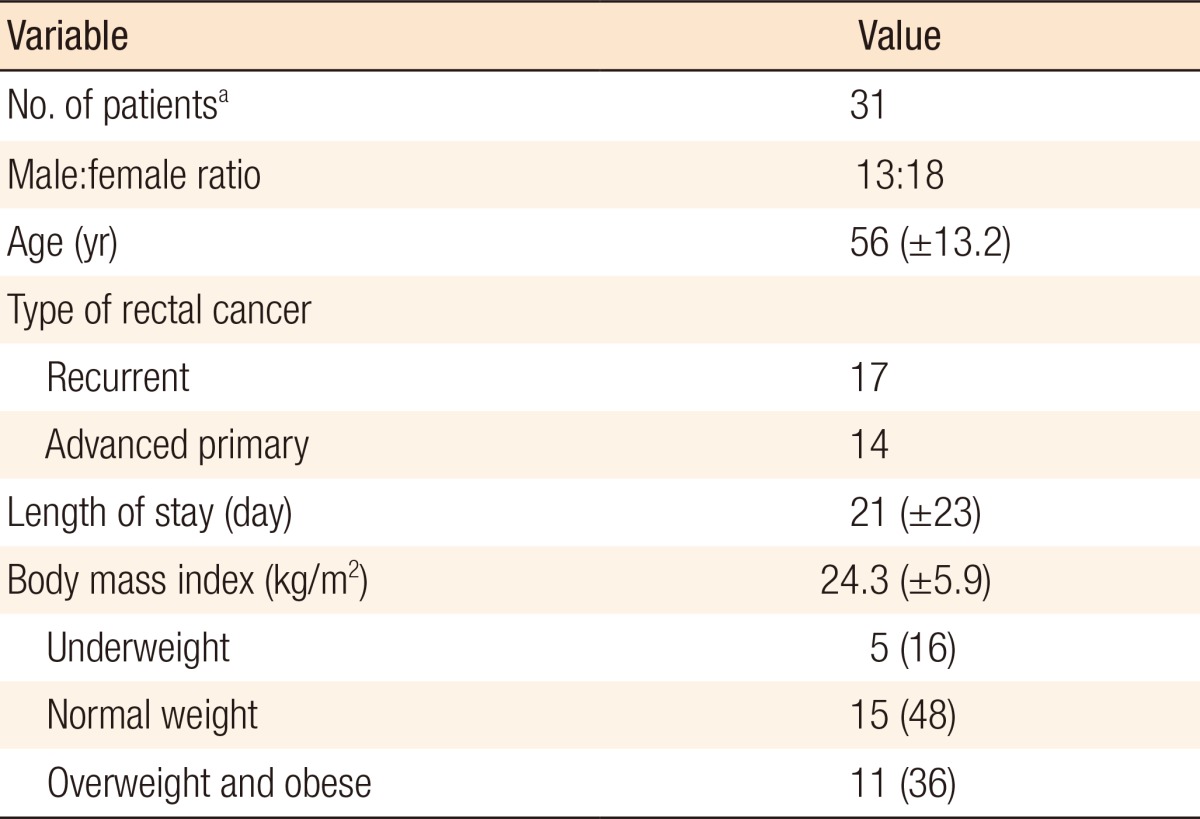

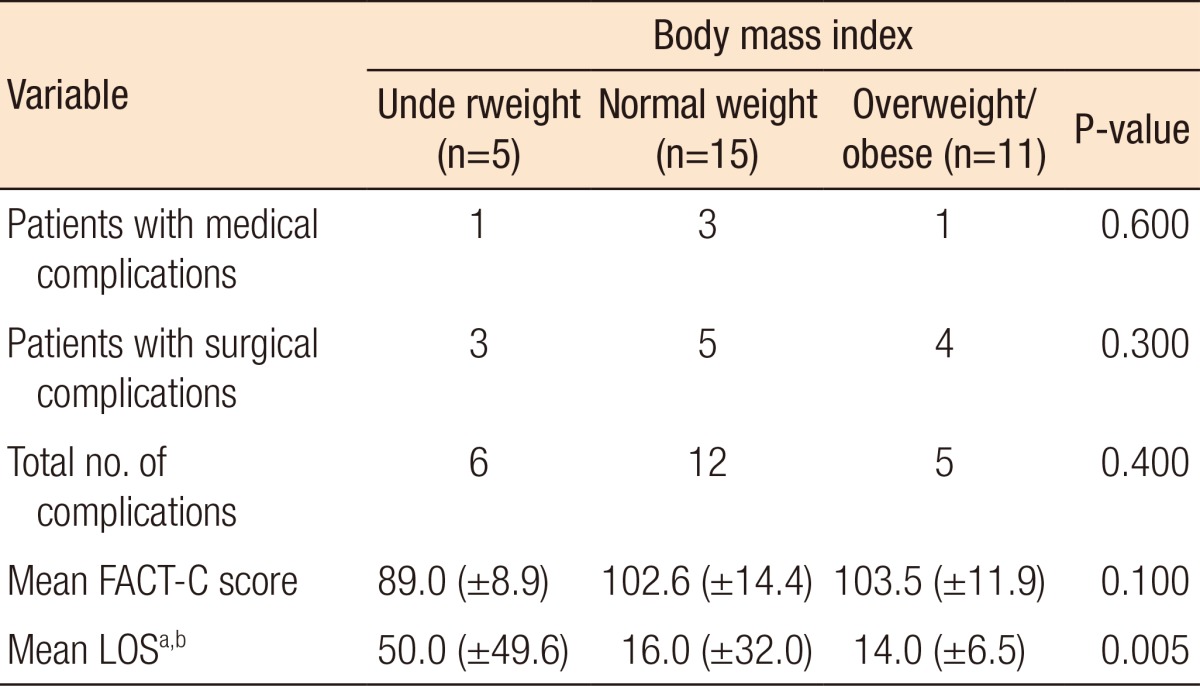

Thirty-one patients, with a mean age of 56 years, had preoperative height and weight data, as well as measures of postoperative QoL, and formed the study group. The numbers of patients with recurrent (n = 17) or locally-advanced rectal cancer (n = 14) were similar. The mean length of stay was 21 days while the mean BMI of the patients was 24.3 (± 5.9) kg/m2. The majority of the patients were either of normal weight (n = 15) or overweight/obese (n = 11). The average length of hospital stay was significantly longer in patients who were underweight compared to those who were of normal weight (F = 6.508, P = 0.006) and those who were overweight and obese (F = 6.508, P = 0.007).

Malnutrition is prevalent in patients before and after gastrointestinal surgery and has been associated with an increased incidence of postoperative morbidity [1, 2, 3, 4, 5] and mortality [5, 6]. The detrimental effects of malnutrition on postoperative recovery following gastrointestinal surgery can include compromised organ function [1], impaired immune function [1], delayed wound healing [7], and increased length of hospital stay [2]. In the colorectal cancer population specifically, rates of malnutrition have been documented to be between 20%-56% [8, 9, 10, 11]; malnutrition is associated with poorer outcomes [1, 2, 12] and reduced quality of life (QoL) [13]. While nutritional status and malnutrition are ideally measured using multifaceted tools, including the subjective global assessment (SGA) [14], the body mass index (BMI) is the standard anthropometric measure of health and nutrition [15], and it has previously been associated with morbidity and mortality in post-surgical patients [6, 16].

Pelvic exenteration surgery is a radical procedure that offers curative potential for recurrent rectal cancer and locally advanced rectal cancer [17]. As surgery in these patients is their only hope of cure, pelvic exenteration surgeries are being increasingly performed. Such radical surgery involves complete or partial removal of all the pelvic viscera, vessels, muscles and ligaments; also, removal of part of the pelvic bone may be required. It has previously been associated with significant morbidity and mortality [18, 19, 20]. Centers in Australia have reported acceptable peri-operative morbidity and mortality rates, 27% and 0.6%, respectively, and 5-year survival rates between 36%-46% [21, 22]. Without resection these patients have a poor prognosis, and only 3% will survive 5 years [23].

Currently no information is available in the literature either on the association between preoperative nutritional status and postoperative morbidity and mortality or on the impact of preoperative nutritional status on measures of QoL in pelvic exenteration surgery specifically. Therefore, the aim of this retrospective study was to determine, prior to embarking on a large prospective nutritional assessment and surgical outcome study, whether or not preoperative BMI was associated with 30-day morbidity and/or QoL in patients' undergoing pelvic exenteration surgery for recurrent or locally advanced rectal cancer.

Patients who underwent pelvic exenteration surgery from January 1996 to November 2007 were identified from colorectal department records for this retrospective study. Medical records and a colorectal prospective exenteration database were used to collect data on nutritional status, morbidity and QoL. This study was approved by the Royal Prince Alfred Hospital's Ethics Committee.

Nutritional status was assessed using weight, height, and BMI. Preoperative weight and height measurements were recorded retrospectively from admission notes in the hospital medical records. The BMI was calculated using the standard formula height (kg)/height (m2). World Health Organization classifications were used to determine underweight (<18.5 kg/m2), normal weight (18.5-24.99 kg/m2) and overweight and obese (>25.0 kg/m2) BMI ranges [15]. When patients were older than 65 years of age, the normal weight range 22-27 kg/m2 was used [24].

QoL was measured using the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy - Colorectal (FACT-C) questionnaire [25]. The FACT-C is a widely used cancer-specific QoL instrument that comprises 27 items pertaining to physical, social, emotional and functional well being and a further 10 items that are specific to colorectal cancer, including bowel function, appetite, digestion, and concerns about ostomies. The FACT-C is a valid and reliable measure of QoL in colorectal cancer patients and is sensitive to changes in functional status [25]. The FACT-C scores range from 0 to 136, with a higher score reflecting a better quality of life [25].

The 30-day morbidity, measured in the form of total number of complications, was collected from the Colorectal Department's exenteration database. The total number and the types of complications for each patient were recorded. Postoperative complications were either surgical (abdominal or pelvic collections, anastomotic leak, enterocutaneous fistula, wound infections, superficial wound dehiscence, deep wound dehiscence, prolonged ileus, small bowel obstruction, ureteric injury, incontinence, splenectomy, septicaemia, postoperative hemorrhage, multiresistant staphylococcus aureus, vancomycin resistant enterococcus, and others) or medical (deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolus, cardiac complications, chest infection, pneumothorax, acute confusion, cardiovascular accident, pressure sores, and others). The length of stay was defined as the duration of inpatient hospital stay with the day of surgery being taken as day 0.

Data was collected on a predesigned data collection form, deidentified, entered into and analyzed by using the PASW ver. 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Descriptive statistics were expressed as means and standard deviations. Pearson correlation coefficient was used to determine associations between the BMI and the QoL. Differences between the BMI and complications and length of stay (LOS) were assessed using unpaired t-tests and analysis of variance using Tukey post hoc analysis. The demographic characteristics of patients with available BMI and QoL data were compared with those of patients who were excluded due to missing data by using the chi-square and the unpaired t-tests to investigate potential selection bias. A P-value of <0.05 was considered significant for all analyses.

Thirty-one patients had full weight and height data recorded in the medical notes at the time of surgery and had completed the FACT-C QoL questionnaire. For these 31 patients, the median time of completion of the FACT-C postpelvic exenteration surgery was 47 months (range, 1-206 months). The demographic profile of the patients and their nutritional status as determined are summarized in Table 1. There were no significant differences in the demographic characteristics of patients who had BMI and QoL information available compared to those who did not.

Differences in postoperative complications, FACT-C scores and LOS across the BMI categories are shown in Table 2. There was a significant difference between length of stay in patients who were underweight compared to patients of normal weight (F = 6.508, P = 0.007) and those who were overweight or obese (F = 6.508, P = 0.006). The mean FACT-C score for all patients was 100.7 ± 13.5, indicating a good QoL. There was no correlation between preoperative BMI and the total FACT-C score (r = 0.183, P = 0.324). Preoperative BMI was not significantly related to surgical or medical complications. However, further analysis of preoperative BMI and the total number of complications showed patients with two or more complications trended towards having a lower BMI (19.9 ± 2.6 kg/m2) compared with patients who had less than two complications (25.2 ± 6.0 kg/m2) (t = 1.888, P = 0.07), although this difference was not statistically significant.

This retrospective analysis is one of the first studies to investigate the nutritional status of patients undergoing pelvic exenteration surgery for rectal cancer and both its association with the 30-day morbidity and its impact on measures of QoL. According to their BMI, almost half of the patients in this study were within the normal weight range, 16% were underweight and 36% were either overweight or obese. Despite the small number of patients in the current study, similar BMI ranges in the colorectal cancer population have been described elsewhere [8, 11, 26]. When comparing preoperative BMI and LOS in this study, there were significant differences between patients who were underweight and patients who were of normal weight or overweight and obese. Underweight patients were in hospital three times longer than patients who were normal weight or who were overweight or obese. This is similar to a previous study of patients undergoing gastrointestinal surgery where malnourished patients were hospitalized twice as long as their well-nourished counterparts [2]. Although not statistically significant, a trend was seen with BMI and an increase in the total number of complications. Patients with a BMI classified as overweight before surgery in this study had a lower number of complications compared to patients with a BMI at the lower limit of the healthy-weight range. This is consistent with previous studies showing that a higher BMI is associated with a better outcome [6]. In a much larger study investigating the impact of BMI on perioperative outcomes in 2,258 patients undergoing major intra-abdominal surgery, including 753 who were having surgery for rectal cancer, 25.4% were classified as obese, which was not a risk factor for death or major complications. However, underweight patients were found to have a fivefold increase in postoperative mortality [6]. Therefore, while a BMI within the healthy-weight range is recommended for the general population, a higher BMI leading up to major surgery might be of benefit.

Again, limited information exists in the literature regarding patients' expected QoL before and after pelvic exenteration surgery for rectal cancer, and no information is available regarding the association between nutritional status and QoL in this patient group. Previous research investigating the same study group suggested that longer-term survivors of pelvic exenteration have a reasonable QoL compared with patients undergoing a routine resection of a rectal primary cancer and with the Australian population at large [27]. In this study, using a similar patient group, there was no significant difference between preoperative BMI and QOL when using the FACT-C QOL score. Previous studies including nonsurgical colorectal cancer patients have shown associations between nutritional status and QoL, indicating a poorer QoL in malnourished patients [10, 28]. A limitation to consider is that the QoL scores in our study were measured at only one time point in a patient's recovery and that the time from pelvic exenteration varied between patients. The QoL measures were from survivors of pelvic exenteration only and may have overestimated the QoL, because those with the worst outcome (i.e., death) were not measured.

Further limitations need to be considered. Due to the retrospective nature of this study and the limited data available, only a small sample of patients was investigated. In addition, very limited nutritional information was available from the review of the medical notes; only preoperative BMI could be collected, and an alternative surgical group was not available for comparison. Insufficient information was available regarding weight history or serum albumin prior to or after pelvic exenteration. BMI has been criticized as a poor marker of nutritional status as it does not reflect changes in weight, fat free mass [29] or nutritional intake. Previous research has shown that despite having a normal or high BMI, colorectal cancer patients can be considered malnourished [8, 11]. Using validated measures to assess nutritional status, including the SGA would be ideal. Nutritional status, as measured by using the widely adopted and validated SGA tool [14], has been demonstrated to predict postoperative nutrition-related complications in patients undergoing gastrointestinal surgery [2, 4]. In addition, selection bias may be present as some patients may have remained unwell following the operation and, hence, not have been able to complete the questionnaire. Because of the limitations in this retrospective review, a prospective study examining patients' QoL, outcomes and nutritional status by using a variety of validated measures preoperatively and postoperatively, while in hospital and following discharge has been underway since 2008.

This study suggests a lower BMI preoperatively is associated with a longer length of hospital stay and a trend towards a greater number of postoperative complications following pelvic exenteration for rectal cancer. Also, the nutritional status was not associated with long-term QoL in this patient group. However, the many limitations of this study indicate that further prospective research is essential to determine the nutritional status of patients before and after pelvic exenteration for rectal cancer and its association with postoperative outcomes. This will help to better tailor nutrition-assessment practices and nutrition interventions for these patients.

References

1. Sungurtekin H, Sungurtekin U, Balci C, Zencir M, Erdem E. The influence of nutritional status on complications after major intraabdominal surgery. J Am Coll Nutr 2004;23:227–232. PMID: 15190047.

2. Garth AK, Newsome CM, Simmance N, Crowe TC. Nutritional status, nutrition practices and post-operative complications in patients with gastrointestinal cancer. J Hum Nutr Diet 2010;23:393–401. PMID: 20337847.

3. Edington J, Kon P, Martyn CN. Prevalence of malnutrition after major surgery. J Hum Nutr Diet 1997;10:111–116.

4. Detsky AS, Baker JP, O'Rourke K, Johnston N, Whitwell J, Mendelson RA, et al. Predicting nutrition-associated complications for patients undergoing gastrointestinal surgery. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 1987;11:440–446. PMID: 3656631.

5. Makela JT, Kellosalo J, Laitinen SO, Kairaluoma MI. Morbidity and mortality after abdominal operations for cancer. Hepatogastroenterology 1992;39:420–423. PMID: 1459522.

6. Mullen JT, Davenport DL, Hutter MM, Hosokawa PW, Henderson WG, Khuri SF, et al. Impact of body mass index on perioperative outcomes in patients undergoing major intra-abdominal cancer surgery. Ann Surg Oncol 2008;15:2164–2172. PMID: 18548313.

7. Haydock DA, Hill GL. Impaired wound healing in surgical patients with varying degrees of malnutrition. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 1986;10:550–554. PMID: 3098996.

8. Burden ST, Hill J, Shaffer JL, Todd C. Nutritional status of preoperative colorectal cancer patients. J Hum Nutr Diet 2010;23:402–407. PMID: 20487172.

9. Gupta D, Lammersfeld CA, Vashi PG, Burrows J, Lis CG, Grutsch JF. Prognostic significance of Subjective Global Assessment (SGA) in advanced colorectal cancer. Eur J Clin Nutr 2005;59:35–40. PMID: 15252422.

10. Gupta D, Lis CG, Granick J, Grutsch JF, Vashi PG, Lammersfeld CA. Malnutrition was associated with poor quality of life in colorectal cancer: a retrospective analysis. J Clin Epidemiol 2006;59:704–709. PMID: 16765273.

11. Read JA, Choy ST, Beale PJ, Clarke SJ. Evaluation of nutritional and inflammatory status of advanced colorectal cancer patients and its correlation with survival. Nutr Cancer 2006;55:78–85. PMID: 16965244.

12. Brown SC, Abraham JS, Walsh S, Sykes PA. Risk factors and operative mortality in surgery for colorectal cancer. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 1991;73:269–272. PMID: 1929123.

13. Larsson J, Akerlind I, Permerth J, Hornqvist JO. Impact of nutritional state on quality of life in surgical patients. Nutrition 1995;11(2 Suppl): 217–220. PMID: 7626906.

14. Detsky AS, McLaughlin JR, Baker JP, Johnston N, Whittaker S, Mendelson RA, et al. What is subjective global assessment of nutritional status? JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 1987;11:8–13. PMID: 3820522.

15. World Health Organisation. Physical status: the use and interpretation of anthropometry. Report of a WHO Expert Committee. WHO Technical Report Series 854. Geneva: World Health Organisiation; 1995.

16. Gupta R, Knobel D, Gunabushanam V, Agaba E, Ritter G, Marini C, et al. The effect of low body mass index on outcome in critically ill surgical patients. Nutr Clin Pract 2011;26:593–597. PMID: 21947642.

17. Madoff RD. Extended resections for advanced rectal cancer. Br J Surg 2006;93:1311–1312. PMID: 17058323.

18. Rodriguwz-Bigas MA, Petrelli NJ. Pelvic exenteration and its modifications. Am J Surg 1996;171:293–298. PMID: 8619471.

19. Lopez MJ, Standiford SB, Skibba JL. Total pelvic exenteration. A 50-year experience at the Ellis Fischel Cancer Center. Arch Surg 1994;129:390–395. PMID: 8154965.

20. Yu HH, Leong CH, Ong GB. Pelvic exenteration for advanced pelvic malignancies. Aust N Z J Surg 1976;46:197–201. PMID: 1070292.

21. Heriot AG, Byrne CM, Lee P, Dobbs B, Tilney H, Solomon MJ, et al. Extended radical resection: the choice for locally recurrent rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum 2008;51:284–291. PMID: 18204879.

22. Austin KK, Solomon MJ. Pelvic exenteration with en bloc iliac vessel resection for lateral pelvic wall involvement. Dis Colon Rectum 2009;52:1223–1233. PMID: 19571697.

23. Dobrowsky W, Schmid AP. Radiotherapy of presacral recurrence following radical surgery for rectal carcinoma. Dis Colon Rectum 1985;28:917–919. PMID: 4064850.

24. Nutrition Screening Initiative. Nutrition Interventions manual for professionals caring for older Americans. Washington, DC: Nutrition Screening Initiative; 2002.

25. Ward WL, Hahn EA, Mo F, Hernandez L, Tulsky DS, Cella D. Reliability and validity of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Colorectal (FACT-C) quality of life instrument. Qual Life Res 1999;8:181–195. PMID: 10472150.

26. Healy LA, Ryan AM, Sutton E, Younger K, Mehigan B, Stephens R, et al. Impact of obesity on surgical and oncological outcomes in the management of colorectal cancer. Int J Colorectal Dis 2010;25:1293–1299. PMID: 20563875.

27. Austin KK, Young JM, Solomon MJ. Quality of life of survivors after pelvic exenteration for rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum 2010;53:1121–1126. PMID: 20628274.

28. Ravasco P, Monteiro-Grillo I, Vidal PM, Camilo ME. Cancer: disease and nutrition are key determinants of patients' quality of life. Support Care Cancer 2004;12:246–252. PMID: 14997369.

29. Garn SM, Leonard WR, Hawthorne VM. Three limitations of the body mass index. Am J Clin Nutr 1986;44:996–997. PMID: 3788846.