- Search

|

|

Abstract

Purpose

Currently, neoadjuvant chemoradiation (CRT) followed by total mesorectal resection is considered the standard of care for treating locally advanced rectal cancer. This study aimed to investigate the efficacy and feasibility of adding induction chemotherapy to neoadjuvant CRT in locally advanced rectal cancer.

Methods

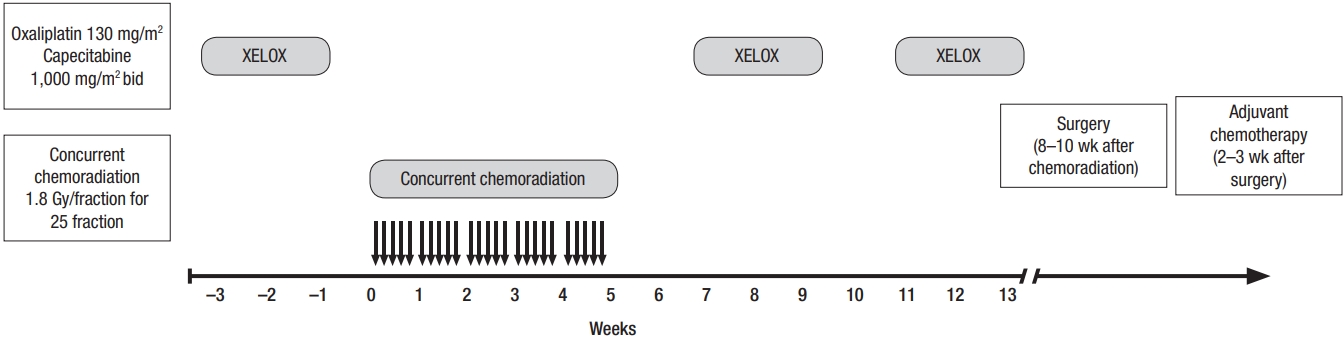

This phase-II clinical trial included 54 patients with newly diagnosed, locally advanced (clinical T3–4 and/or N1–2, M0) rectal cancer. All patients were treated with 3 cycles of preoperative chemotherapy using the XELOX (capecitabine + oxaliplatin) regimen before and after a concurrent standard long course of CRT (45–50.4 Gy) followed by standard radical surgery. Pathologic complete response (PCR) rate and toxicity were the primary and secondary endpoints, respectively.

Results

The study participants included 37 males and 17 females, with a median age of 59 years (range, 20–80 years). Twenty-nine patients (54%) had clinical stage-II disease, and 25 patients (46%) had clinical stage-III disease. Larger tumor size (P = 0.006) and distal rectal location (P = 0.009) showed lower PCR compared to smaller tumor size and upper rectal location. Pathologic examinations showed significant tumor regression (6.1 ± 2.7 cm vs. 1.9 ± 1.8 cm, P < 0.001) with 10 PCRs (18.5%) compared to before the intervention. The surgical margin was free of cancer in 52 patients (96.3%). Treatment-related toxicities were easily tolerated, and all patients completed their planned treatment without interruption. Grade III and IV toxicities were infrequent.

Currently, neoadjuvant chemoradiation (CRT) followed by total mesorectal excision (TME) is considered the standard of care for achieving optimal local control in locally advanced (T3–4 and/or N1–2) rectal cancer [1]. Traditionally, this treatment approach is followed by six months of adjuvant chemotherapy. Pathologic complete response (PCR) is an important marker for the efficacy of neoadjuvant treatment. This indicator frequently is used in phase II and III clinical trials to evaluate the efficacy of treatment modalities in cancer patients [2]. PCR and tumor down staging following neoadjuvant CRT have been associated with improved survival in several neoadjuvant studies. Large scale multicenter studies confirmed PCR as a potent indicator for predicting locoregional control and 5-year disease-free and overall survival [3, 4]. While the impact of neoadjuvant CRT on overall survival is not yet established; adjuvant chemotherapy following neoadjuvant CRT and surgery improves survival [5, 6]. However, adjuvant chemotherapy following CRT and surgery is associated with higher toxicity and lower patient compliance. On the other hand, neoadjuvant chemotherapy induces tumor shrinkage and facilitates surgical resection [7]. Few small reports found neoadjuvant chemotherapy alone is safe and effective and may be a potential alternative choice for neoadjuvant CRT in selected cases with locally advanced rectal cancer [8-10]. This study aimed to investigate the feasibility and efficacy of induction chemotherapy preceding CRT and surgery in patients with locally advanced rectal cancer.

This phase II clinical trial was conducted on 54 patients with locally advanced rectal cancer who had been treated at Namazi Hospital, a tertiary academic center, between September 2016 and December 2017. The patients’ performance statuses were scored according to the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance scaling system. Eligible patients had newly diagnosed, locally advanced (clinical T3–4 and/or N1–2, M0) rectal adenocarcinoma, no prior therapy, ECOG performance scale ≤1, and normal or acceptable kidney, liver, cardiovascular, and bone marrow function. Patients with metastatic disease at presentation or previous history of pelvic irradiation were excluded. The study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Namazi Hospital, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences in accordance with the code of ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki) for experiments involving humans (Ethic code no: IR.SUMS.MED.REC.1395.23). Furthermore, written informed consent was obtained from all patients before entering the trial. This clinical trial was approved and supported by Shiraz University of Medical Sciences (research project number: 94-P-9514). In addition, the study was registered on the Iranian Registration of Clinical Trial (IRCT) website on 24 September 2016 (IRCT registration number: IRCT2016082129403N2). Tumor staging was performed using the eighth edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer TNM (AJCC) staging system [11]. Clinical staging was performed using imaging studies for all patients before starting the neoadjuvant intervention. Preliminary evaluation involved comprehensive history and physical examination, including careful rectal examination, colonoscopy, complete blood cell count, liver and renal function studies, carcinoembryonic antigen, chest, abdominal, and pelvic multidetector computed tomography scans, and pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and/or endorectal ultrasonography. Tumor size and location and distal tumor margin from the anal verge were defined based on the findings of endoscopy and MRI. PCR rate and treatment-related toxicity were the primary and secondary endpoints of the study, respectively. Acute treatment-related toxicities, including radiation dermatitis, diarrhea, noninfective cystitis, handfoot syndrome, and bone marrow suppression were recorded according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, ver. 4.30. Clinical response was evaluated by colonoscopy and imaging after neoadjuvant therapy and before surgery. Clinical complete response was defined as complete clinical and radiologic disappearance of the primary tumor and regional lymph nodes. Clinical partial response was defined as at least 30% tumor shrinkage. Clinical tumor response less than 30% tumor shrinkage was defined as no response or stable disease. The grade of tumor regression was evaluated based on the 4 AJCC tumor regression grading (TRG) classifications (Table 1).

Chemotherapy consisted of oral capecitabine 1,000 mg/m2 twice daily for 14 days of every 3-week cycle plus oxaliplatin 130 mg/m2 intravenously on day 1 (XELOX regimen). Additionally, for concurrent CRT, oral capecitabine monotherapy was administered.

Concurrent neoadjuvant CRT consisted of conventional external beam radiation therapy using megavoltage linear accelerator photons. The photon energy was 18 MV in a three-field (one direct posterior and two lateral fields) or four-field technique (AP-PA parallel opposed fields and 2 lateral opposed fields). All patients were treated in the prone position with a full bladder to reduce small bowel toxicity. A median dose of 45 Gy (range, 45–50.4 Gy) was delivered via a daily fraction of 1.8–2 Gy with 5 fractions per week. Concurrent chemotherapy consisted of oral capecitabine 825 mg/m2 twice daily during the whole period of pelvic radiotherapy with weekend breaks. Two weeks after the completion of radiation, 2 cycles of consolidation chemotherapy (XELOX regimen) were administered and all patients were subsequently referred for surgery with a median 8 weeks (range, 8–10 weeks) interval after the last session of radiation therapy.

A standard curative surgery through TME was performed as a part of a low anterior resection (LAR) or an abdominoperineal resection (APR) procedure for all patients. A colorectal surgeon performed all rectal surgeries. Pathologic response was assessed after curative surgery. PCR was defined as the disappearance of all invasive tumors, either on a macroscopic or a microscopic scale, in the rectum and lymph nodes. Two weeks after surgery, all patients received 3 cycles of adjuvant chemotherapy regardless of achieved response to neoadjuvant therapy.

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics ver. 22.0 (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA). Chi-square, Fisher exact, and Mann-Whitney tests were used for comparing the clinical and pathological response rates and the categorical clinicopathologic characteristics of the patients as appropriate. Additionally, the Student t-test was used for comparing continuous variables, such as age, tumor size, and radiation dose. According to previous studies, a sample size less than 50 patients for analysis was needed [12-14]. All statistical tests were two-sided and P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

This phase-II clinical trial included 54 patients with locally advanced rectal cancer. All patients were treated with curative intent and completed CRT as scheduled. Fig. 1 shows a diagram of the study protocol. The study participants included 37 males and 17 females, with a median age of 59 years (range, 20–80 years). Twenty-nine patients (54%) had clinical stage-II disease, and 25 patients (46%) had clinical stage-III disease. The median clinical tumor size was 5 cm (range, 2–13 cm). Additionally, the median distance from the anal verge was 6 cm (range, 1–15 cm). Table 2 correlates clinicopathological characteristics and PCR rate among the 54 patients with rectal cancer. There was a statistically significant difference between patients who achieved PCR and those who did not in terms of initial clinical tumor size and distance from the anal verge. Larger tumor size (P = 0.006) and distal rectal location (P = 0.009) showed lower PCR compared to smaller tumor size and upper rectal location. Just before surgery, clinical complete and partial response was achieved in 14 patients (26%) and 31 patients (57%), respectively, and 9 patients (17%) had stable disease.

All patients receive a median 3 cycles (range, 3–4 cycles) of preoperative chemotherapy and completed the chemotherapy cycles as scheduled. Three weeks after the last cycle of chemotherapy all patients underwent a LAR (n = 34) or an APR (n = 10). Pathologic examinations showed significant tumor regression (mean, 6.1 ± 2.7 cm vs. 1.9 ± 1.8 cm; P < 0.001) with 10 PCRs (18.5%) compared to before the intervention. However, no significant node response was observed (P = 0.232) compared to the initial clinical stage. Classifications of TRG 0, 1, 2, and 3 were found in 18.5%, 9.3%, 44.4%, and 27.8% of the specimens, respectively. The surgical margin was free of cancer in 52 patients (96.3%) and microscopically involved in 2 patients (3.7%); 1 involving the distal margins in LAR and 1 involving the circumferential resected margins in APR.

Regarding treatment-related toxicity, most patients developed grade-2 dermatitis (57%), grade-1 diarrhea (18%), and grade-1 anemia (35%). However, noninfective cystitis was infrequent. Other hematologic complications, such as neutropenia and thrombocytopenia, were also uncommon (Table 3). Treatmentrelated toxicities were easily tolerated, and all patients completed their planned treatment without interruption. In addition, perioperative and early postoperative surgical complications, such as anastomotic leakage, delayed wound healing, increase in infections, and fistula formation were rare.

Despite advances in neoadjuvant CRT and TME in patients with locally advanced rectal cancer, local recurrence and distant metastasis occur in about 25%–30% and 10%, respectively [7, 15]. In order to enhance tumor shrinkage and minimizing metastasis, induction chemotherapy preceding surgery has been considered with or without CRT in some studies. Induction chemotherapy with or without CRT in locally advanced rectal cancer has many potential advantages including higher rate of PCR and resectability, micrometastasis eradication, minimizing ileostomy duration, and higher rate of patients compliance to complete chemotherapy courses [5, 9, 16]. In this study, we incorporated a median of three cycles of induction chemotherapy to standard neoadjuvant CRT to investigate this treatment approach in patients with rectal cancer.

Some authors believe that radiation therapy increases perioperative morbidity, and induction chemotherapy without radiotherapy may be effective and allow radiation side effects to be avoided [17]. In few recent prospective and retrospective studies, chemotherapy was investigated as the sole neoadjuvant treatment. Chemotherapy was well tolerated in these studies and the main complication was neutropenia. PCR rate was 4%–25%. The rate of complete tumor resection was 92%–100%. The main drawbacks were small number of patients (10–60) and different chemotherapy regimens. In addition, the dose and schedule modification was reported in these studies [8, 17-20]. In our study, the patients tolerated chemotherapy with the XELOX regimen well and grades III–IV bone marrow and gastrointestinal (GI) toxicity was uncommon.

Bevacizumab was also used in combination with chemotherapy in a neoadjuvant setting in one study. In an ongoing randomized phase II trial by Glynne-Jones et al. [10], 60 patients will receive FOLFOX + bevacizumab or FOLFOX + irinotecan (FOLFOXIRI) + bevacizumab. All patients will receive chemotherapy for 6 cycles and bevacizumab will be discontinued in the last cycle to avoid postoperative complications such as anastomotic leakage. One of the weaknesses in our study was the lack of assessment of postoperative complications.

The multicenter PROSPECT trial (N1048, available at www. ctsu.org) has been designed to confirm the efficacy and feasibility of preoperative chemotherapy in clinical stage T2N1 or T3N0–1 rectal cancer. In this trial, all patients will receive six cycles of modified FOLFOX6 after which, patients with a clinical response will undergo surgery and nonresponders will receive neoadjuvant or adjuvant CRT. In the PROSPECT trial, patients with clinical stage T4 or N2 disease and those with low-lying tumors needing APR will be excluded. In the present research, we included all clinical stage II–III rectal cancers, and we did not exclude T4 or N2 lesions.

In the largest retrospective study using the National Cancer Database, Cassidy et al. [21] investigated the feasibility of induction combination chemotherapy in selected cases of stage II or III rectal cancer with the aim of eliminating neoadjuvant CRT. Their study included 21,707 patients with clinical stage T2N1 or T3N0–1 rectal cancer treated with neoadjuvant CRT (n = 21,433) or neoadjuvant combination chemotherapy alone (n = 272). Using Cox-proportional hazards regression analyses they found a significantly higher 5-year actuarial overall survival rate (75% vs. 67.2%) in favor of the CRT arm. Therefore, they concluded induction chemotherapy alone even in selected cases with low risk stages II–III rectal cancer should be restricted in the context of a clinical trial.

However, other studies investigated induction chemotherapy in combination with neoadjuvant CRT in patients with locally advanced rectal cancer. Most of these trials found induction chemotherapy enhanced tumor shrinkage and PCR rate with treatable toxicities. Table 4 illustrates the rates of PCR and R0 resection in these recent clinical trials and compares their results with those of the present study [7, 12, 14, 15, 22-28]. Accordingly, our study shows comparable results in terms of PCR and R0 resection compared to previous reports.

Preliminary results of the FORWARC Chinese multicenter clinical trial showed modified FOLFOX (mFOLFOX) combined with CRT provided a significantly higher rate (31.3%) of PCR compared to induction mFOLFOX alone (7.4%); however, induction mFOLFOX6 alone resulted in similar tumor down-staging with lower treatment toxicity and postoperative complications. According to the results of these clinical trials and the current study, the addition of induction chemotherapy to neoadjuvant CRT is associated with a higher rate of PCR and disease-free surgical margins compared to the results of historical reports [29]. It seems an infusional chemotherapy regimen such as mFOLFOX and further chemotherapy cycles can achieve a higher PCR rate; however, its impact on oncologic outcomes should be confirmed by large prospective studies.

The limitations of our phase II study include a relatively small sample size and single arm design and the use of conventional radiotherapy instead of newer modalities such as intensity-modulated radiotherapy. Furthermore, most patients in this study received a lower median total radiation dose (45 Gy) compared to those (50.4–54 Gy) in recent studies. Nevertheless, our study provides a well-tolerated alternative treatment approach to the current standard neoadjuvant CRT alone regimen in patients with rectal cancer.

This phase II clinical trial concluded that the addition of preoperative chemotherapy with the XELOX regimen to neoadjuvant CRT in locally advanced rectal cancer is an effective and well-tolerated treatment approach in patients with rectal cancer. However, a larger multicentric phase III clinical trial with longer follow-up is warranted to confirm our findings and evaluate the impact of this treatment strategy on oncologic outcomes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This manuscript is part of a thesis by Sepideh Mirzaei. Shiraz University of Medical Sciences supported this study. The authors would like to thank Ms. A. Keivanshekouh at the Research Improvement Center of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences for improving the use of English in the manuscript.

Table 1.

American Joint Committee on Cancer TRG

Table 2.

Correlation between clinicopathological characteristics and PCR to therapy

| Variable | PCR | No PCR | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 0.105a | ||

| Male | 9 | 26 | |

| Female | 1 | 16 | |

| Age (yr) | 57.7 ± 15.9 | 59.6 ± 11.9 | 0.670*,b |

| Clinical tumor size (cm) | 4.0 ± 1.2 | 6.5 ± 2.7 | 0.006*,b |

| Distance from anal verge (cm) | 10.1 ± 4.2 | 6.4 ± 3.5 | 0.009*,b |

| Clinical tumor stage | 0.262a | ||

| T2 | 1 | 1 | |

| T3 | 8 | 30 | |

| T4 | 1 | 13 | |

| Clinical node stage | 0.252a | ||

| Negative | 7 | 22 | |

| Positive | 3 | 22 | |

| Tumor grade | 0.239a | ||

| I | 7 | 30 | |

| II | 0 | 12 | |

| III | 0 | 1 | |

| Radiotherapy dose (Gy) | 44.5 ± 7.3 | 46.8 ± 2.5 | 0.100b |

| Type of surgery | 0.034*,a | ||

| Low anterior resection | 10 | 24 | |

| Abdominoperineal resection | 0 | 10 |

Table 3.

Rate of treatment-related toxicity in 54 patients with rectal cancer

Table 4.

Recent clinical trials investigating the combination of induction chemotherapy and neoadjuvant chemoradiation in locally advanced rectal cancer

| Study | No. of patients | ChT × cycles | Rate of PCR (%) | Rate of R0 resection (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cercek et al. [28] | 49 | mFOLFOX × 7 | 26.5 | 100 |

| Chau et al. [22] | 77 | XELOX × 4 | 24 | 98.7 |

| Deng et al. [27] | 149 | mFOLFOX × 5 | 31.3 | 88.2 |

| Eisterer et al. [23] | 25 | XELOX × 3 | 25 | 95 |

| Fernandez-Martos et al. [7] | 56 | XELOX × 4 | 14.3 | 86 |

| Koeberle et al. [14] | 58 | XELOX × 3 | 23 | 98 |

| Larsen et al. [15] | 52 | XELOX × 6 | 20 | 100 |

| Marechal et al. [26] | 28 | mFOLFOX × 2 | 32.1 | NS |

| Moore et al. [24] | 25 | XELOX × 3 | 16 | NS |

| Nogue et al. [25] | 45 | XELOX × 3 | 36 | 98 |

| Perez et al. [12] | 39 | mFOLFOX × 8 | 33 | NS |

| This study | 54 | XELOX × 3 | 18.5 | 96.3 |

REFERENCES

1. Rule W, Meyer J. Current status of radiation therapy for the management of rectal cancer. Crit Rev Oncog 2012;17:331–43.

2. Fu XL, Fang Z, Shu LH, Tao GQ, Wang JQ, Rui ZL, et al. Metaanalysis of oxaliplatin-based versus fluorouracil-based neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy and adjuvant chemotherapy for locally advanced rectal cancer. Oncotarget 2017;8:34340–51.

3. Capirci C, Valentini V, Cionini L, De Paoli A, Rodel C, GlynneJones R, et al. Prognostic value of pathologic complete response after neoadjuvant therapy in locally advanced rectal cancer: longterm analysis of 566 ypCR patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2008;72:99–107.

4. Maas M, Nelemans PJ, Valentini V, Das P, Rodel C, Kuo LJ, et al. Long-term outcome in patients with a pathological complete response after chemoradiation for rectal cancer: a pooled analysis of individual patient data. Lancet Oncol 2010;11:835–44.

5. Aschele C, Cionini L, Lonardi S, Pinto C, Cordio S, Rosati G, et al. Primary tumor response to preoperative chemoradiation with or without oxaliplatin in locally advanced rectal cancer: pathologic results of the STAR-01 randomized phase III trial. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:2773–80.

6. Lichthardt S, Zenorini L, Wagner J, Baur J, Kerscher A, Matthes N, et al. Impact of adjuvant chemotherapy after neoadjuvant radioor radiochemotherapy for patients with locally advanced rectal cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2017;143:2363–73.

7. Fernandez-Martos C, Pericay C, Aparicio J, Salud A, Safont M, Massuti B, et al. Phase II, randomized study of concomitant chemoradiotherapy followed by surgery and adjuvant capecitabine plus oxaliplatin (CAPOX) compared with induction CAPOX followed by concomitant chemoradiotherapy and surgery in magnetic resonance imaging-defined, locally advanced rectal cancer: Grupo cancer de recto 3 study. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:859–65.

8. Hasegawa S, Goto S, Matsumoto T, Hida K, Kawada K, Matsusue R, et al. A multicenter phase 2 study on the feasibility and efficacy of neoadjuvant chemotherapy without radiotherapy for locally advanced rectal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 2017;24:3587–95.

9. Jalil O, Claydon L, Arulampalam T. Review of neoadjuvant chemotherapy alone in locally advanced rectal cancer. J Gastrointest Cancer 2015;46:219–36.

10. Glynne-Jones R, Anyamene N, Moran B, Harrison M. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy in MRI-staged high-risk rectal cancer in addition to or as an alternative to preoperative chemoradiation? Ann Oncol 2012;23:2517–26.

11. In: Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, Fritz AG, Greene FL, Trotti III A. editors. AJCC cancer staging manual. 7th ed. New York: Springier; 2010.

12. Perez K, Safran H, Sikov W, Vrees M, Klipfel A, Shah N, et al. Complete neoadjuvant treatment for rectal cancer: the Brown University oncology group CONTRE study. Am J Clin Oncol 2017;40:283–7.

13. Nishimura J, Hasegawa J, Kato T, Yoshioka S, Noura S, Kagawa Y, et al. Phase II trial of capecitabine plus oxaliplatin (CAPOX) as perioperative therapy for locally advanced rectal cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2018;82:707–16.

14. Koeberle D, Burkhard R, von Moos R, Winterhalder R, Hess V, Heitzmann F, et al. Phase II study of capecitabine and oxaliplatin given prior to and concurrently with preoperative pelvic radiotherapy in patients with locally advanced rectal cancer. Br J Cancer 2008;98:1204–9.

15. Larsen FO, Markussen A, Jensen BV, Fromm AL, Vistisen KK, Parner VK, et al. Capecitabine and oxaliplatin before, during, and after radiotherapy for high-risk rectal cancer. Clin Colorectal Cancer 2017;16:e7–14.

16. Schou JV, Larsen FO, Rasch L, Linnemann D, Langhoff J, Hogdall E, et al. Induction chemotherapy with capecitabine and oxaliplatin followed by chemoradiotherapy before total mesorectal excision in patients with locally advanced rectal cancer. Ann Oncol 2012;23:2627–33.

17. Matsumoto T, Hasegawa S, Zaima M, Inoue N, Sakai Y. Outcomes of neoadjuvant chemotherapy without radiation for rectal cancer. Dig Surg 2015;32:275–83.

18. Koike J, Funahashi K, Yoshimatsu K, Yokomizo H, Kan H, Yamada T, et al. Efficacy and safety of neoadjuvant chemotherapy with oxaliplatin, 5-fluorouracil, and levofolinate for T3 or T4 stage II/III rectal cancer: the FACT trial. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2017;79:519–25.

19. Schrag D, Weiser MR, Goodman KA, Gonen M, Cercek A, Reidy DL, et al. Neoadjuvant FOLFOX-bev, without radiation, for locally advanced rectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 2010;28(15_Suppl): 3511.

20. Hata T, Takahashi H, Sakai D, Haraguchi N, Nishimura J, Kudo T, et al. Neoadjuvant CapeOx therapy followed by sphincter-preserving surgery for lower rectal cancer. Surg Today 2017;47:1372–7.

21. Cassidy RJ, Liu Y, Patel K, Zhong J, Steuer CE, Kooby DA, et al. Can we eliminate neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy in favor of neoadjuvant multiagent chemotherapy for select stage II/III rectal adenocarcinomas: analysis of the National Cancer Data Base. Cancer 2017;123:783–93.

22. Chau I, Brown G, Cunningham D, Tait D, Wotherspoon A, Norman AR, et al. Neoadjuvant capecitabine and oxaliplatin followed by synchronous chemoradiation and total mesorectal excision in magnetic resonance imaging-defined poor-risk rectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:668–74.

23. Eisterer W, Piringer G, DE Vries A, Ofner D, Greil R, Tschmelitsch J, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy with capecitabine, oxaliplatin and bevacizumab followed by concomitant chemoradiation and surgical resection in locally advanced rectal cancer with high risk of recurrence: a phase II study. Anticancer Res 2017;37:2683–91.

24. Moore J, Price T, Carruthers S, Selva-Nayagam S, Luck A, Thomas M, et al. Prospective randomized trial of neoadjuvant chemotherapy during the ‘wait period’ following preoperative chemoradiotherapy for rectal cancer: results of the WAIT trial. Colorectal Dis 2017;19:973–9.

25. Nogue M, Salud A, Vicente P, Arrivi A, Roca JM, Losa F, et al. Addition of bevacizumab to XELOX induction therapy plus concomitant capecitabine-based chemoradiotherapy in magnetic resonance imaging-defined poor-prognosis locally advanced rectal cancer: the AVACROSS study. Oncologist 2011;16:614–20.

26. Marechal R, Vos B, Polus M, Delaunoit T, Peeters M, Demetter P, et al. Short course chemotherapy followed by concomitant chemoradiotherapy and surgery in locally advanced rectal cancer: a randomized multicentric phase II study. Ann Oncol 2012;23:1525–30.

27. Deng Y, Chi P, Lan P, Wang L, Chen W, Cui L, et al. Modified FOLFOX6 with or without radiation versus fluorouracil and leucovorin with radiation in neoadjuvant treatment of locally advanced rectal cancer: initial results of the Chinese FOWARC multicenter, open-label, randomized three-arm phase III trial. J Clin Oncol 2016;34:3300–7.